The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to widespread hunger in Alabama. We all have seen the pictures – lines of cars stretching for blocks waiting to receive an emergency food box, desperate appeals from food banks that distributed as much food in the first six months of the pandemic as they did in the prior year, school buses filled with lunches for delivery to hungry children unable to go to school in person. Facebook pages have sprung up to offer desperately needed peer advice on how to navigate the food assistance system.

Hunger is an ugly public face of this pandemic and its associated recession. Amid persistent job and income losses, hundreds of thousands of Alabama families are struggling to keep food on the table.

Where are we now?

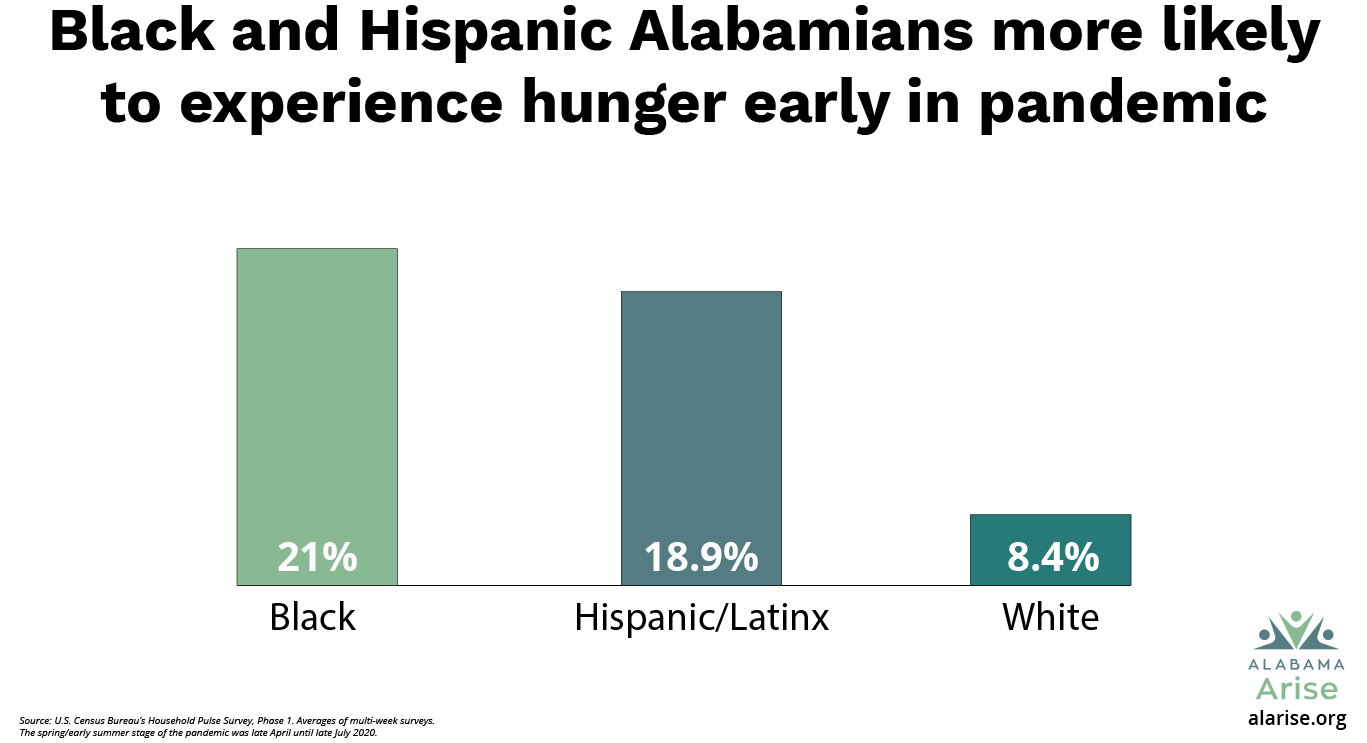

In the spring/early summer stage of the pandemic (late April until late July 2020), 12% of all Alabama families and 13% of Alabama families with children either sometimes or often didn’t have enough food to eat, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.[1] And the hunger challenges were much more serious in communities of color. Nearly 19% of Hispanic/Latinx Alabamians and 21% of Black Alabamians said they didn’t have enough food, compared to slightly more than 8% of white Alabamians.[2]

How did we get here?

Unequal job losses have led to increased hunger. Between mid-August and late October (the late summer/fall stage of the pandemic), one in five Alabamians who reported income loss said they either sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat.[3] This includes a third of the people who reported losing their jobs due to pandemic-related layoffs, plus another third – mostly women – who wanted to return to work but couldn’t because they were caring for children whose schools or day cares were closed due to the pandemic.[4]

The Household Pulse Survey shows both the value and the limitations of critical safety net programs. Nearly three in four (or 74%) of Alabamians who used unemployment insurance (UI) benefits were able to afford their basic food needs during the late summer/fall stage of the pandemic, as were 78% of people who used federal stimulus payments to make ends meet.[5] Two in three Alabamians who received food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) said they had enough food.[6]

High demand at food banks shows need to strengthen nutrition assistance

These and other safety net programs have eased suffering for hundreds of thousands of Alabamians during the pandemic. Even so, significant numbers of people still reported they didn’t have enough to eat.

Revealing the limitations of the safety net, tens of thousands of Alabamians also used emergency food programs and free school meals to feed their families. The week before Thanksgiving, 10% of Pulse Survey respondents in Alabama said they still relied on free groceries in the last week.[7] The largest share of people who relied on emergency food received it from Alabama’s food banks or faith-based and community food pantries (61%), followed by school-based or other programs that provided food to children (31%) and family or friends (27%).[8]

Food banks and other sources of emergency food play a vital role feeding hungry families. But these programs simply cannot meet the scale of need that the COVID-19 recession has caused.

What should we do now?

The state and federal governments can make a number of important public policy changes to help feed Alabama families during this difficult time and beyond:

- Alabama lawmakers should abandon efforts to slash the state’s safety net. The COVID-19 recession has taught many painful lessons about the critical role that safety net programs play during a crisis. Legislators should resist the temptation to introduce and pass bills restricting access to SNAP and other safety net programs. If enacted in past years, these bills would have made the recent hunger and hardship in Alabama even more dire.

- The state departments of Education and Human Resources should move quickly to implement P-EBT for the 2020-21 school year. When schools closed, Congress created the Pandemic EBT (P-EBT) program, which provided debit-like cards with enough money on them to replace the value of lost school meals. Lawmakers later expanded this program in a continuing resolution in September. Now Alabama needs to distribute these desperately needed benefits rapidly to families whose children are going to school remotely or who are in hybrid classrooms.

- Eligible schools in Alabama should reduce childhood hunger by participating in the Community Eligibility Provision for the 2021-22 school year. Community eligibility allows eligible schools to serve meals at no cost to all enrolled students, streamlining the usual paperwork. Participation in community eligibility automatically makes children eligible for P-EBT. And it eases logistical barriers for schools to provide free meals to children who are attending school remotely.

- Congress should move quickly to pass another COVID-19 relief bill that further increases federal UI benefits and SNAP assistance. The bill also should provide additional cash assistance for struggling families, including relief payments, a fully refundable Child Tax Credit and an increased Earned Income Tax Credit.

The State of Working Alabama 2021

Footnotes

[1] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, April 23 – July 21, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 2, Aug. 19 – Oct. 26, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Id.

[7] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Week 19 Household Pulse Survey: Nov. 11 – Nov. 23, Food Sufficiency and Food Security Table 2b, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html.

[8] Ibid.