Where are we now?

The COVID-19 recession hit vulnerable Alabama workers hard and fast. Alabamians working in low-paying industries suffered immediate and severe job losses, which fell hardest on women and people of color. Unemployment insurance (UI), designed for just such a moment, was inadequate and insufficient to the needs of these workers because of Alabama’s policy choices.

By December 2020, after the first nine months of the pandemic, 35,400 fewer Alabamians were employed than in February 2020.[1] That reflects a 1.7% drop in overall employment, which includes people who have dropped out of the labor market. The hardest-hit industry was leisure and hospitality, which lost 19,000 jobs, a 9.1% decline.[2] People working in this industry, which includes restaurants and entertainment establishments, often have fewer educational opportunities and lower incomes. They also are disproportionately women, people of color and younger adults.[3]

Also hard-hit was the education and health industry, which lost 16,600 jobs (a 6.6% decline) and also disproportionately employs women.[4] In Alabama, 81% of health care workers are women, as are 89% of child care and social service workers.[5] Almost instantly as the pandemic struck, Alabama’s official unemployment rate shot up to 13.8%.[6] By December, it had declined to 3.9% – still an increase of 1 percentage point over February 2020.[7]

The precipitous increase in unemployment during the first six months of the COVID-19 recession was nearly five times Alabama’s job loss during the first six months of the Great Recession.[8] Many Alabama workers simply had no cushion to reduce the damage.

Job losses hammered women, people of color

The official unemployment rate masks the true extent of the damage, especially among women and communities of color. The true number of jobless Alabamians is much higher once we also take into account the people temporarily furloughed when their businesses were closed. These are real job and income losses that are not included in the official unemployment rate. By this count, almost two out of every five working-age Alabamians reported they were not working during the spring/early summer stage of the crisis (late April until late July).[9]

In the same period, women and workers of color – especially Black workers – were hit the hardest. Half of women reported they were not working, compared to 43% of men.[10] Nearly 53% of Black respondents reported they were not working, compared to 47% of white people.[11] Hispanic/Latinx respondents reported not working at a rate roughly the same as white respondents.[12]

Joblessness remained elevated above pre-pandemic levels into mid-December, especially for women. While three out of 10 working-age Alabamians reported not working, a full 47% of women were jobless, a number significantly elevated above the 38% of men who were out of work.[13] The large differences in the percentages of men and women working during both the spring/early summer and late summer/fall stages reflect both the concentration of women working in the hardest-hit industries and the impact of child care responsibilities on working women.

UI claims reflect recession’s racial, gender disparities

Alabama’s claims for UI benefits tell a similar story. More than 967,000 initial unemployment claims were filed between the weeks of March 14, 2020, and Feb. 6, 2021.[14] If each claim were from a single worker, that number would be 45% of all employed people in Alabama as of December 2020.[15]

With the U.S. average duration of unemployment at 22.8 weeks[16] and an Alabama initial claim payout rate of 47%,[17] the state would be on pace to pay more than 9.4 million weeks of benefits on claims arising through the week of Feb. 6, 2021, with the same benefit duration and eligibility structure available under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. This is a massive increase over pre-pandemic unemployment.

There were fewer than 2,000 UI claims for the week of March 14, 2020, the claim period immediately before the pandemic began causing widespread business shutdowns. Since then, the average weekly number of UI claims has been 1,105% higher than that amount, as of Feb. 6, 2021.[18]

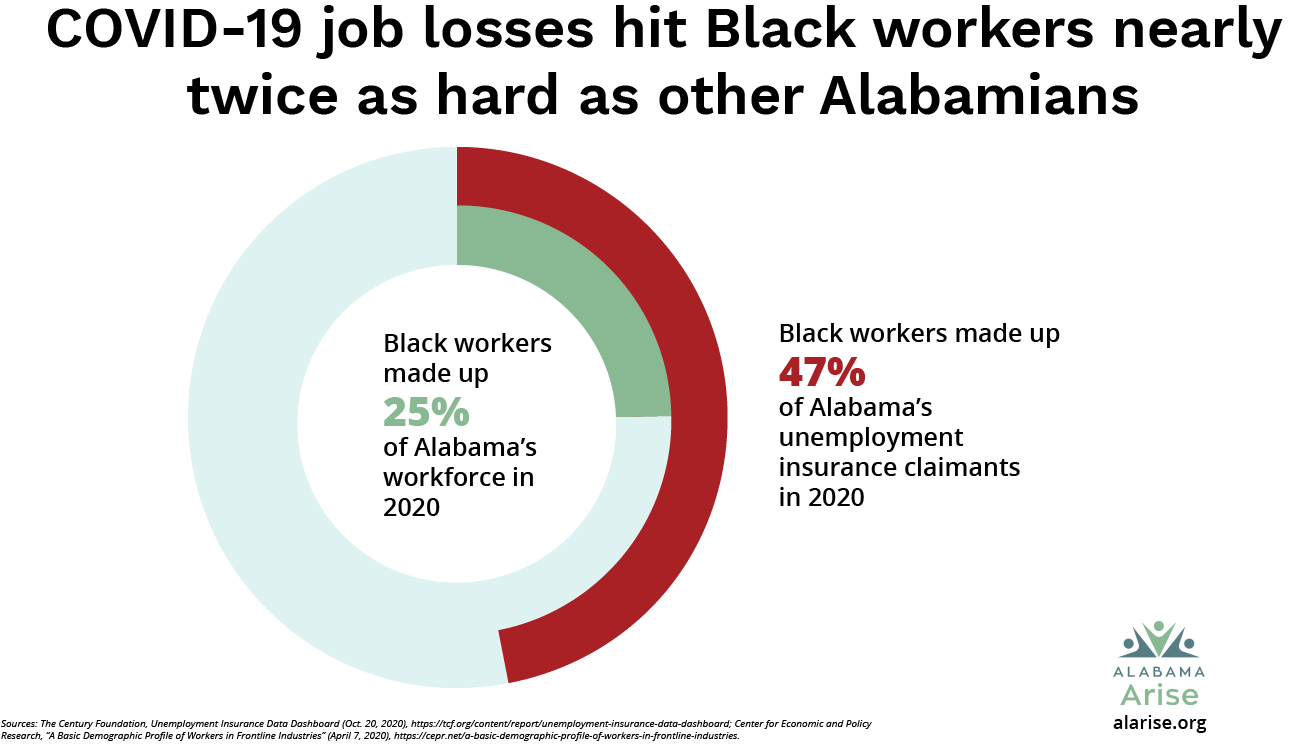

UI claims underscore the racial inequities driving COVID-19’s unequal impact on employment. Black workers lost their jobs because of the COVID-19 pandemic at a much higher rate than their percentage of the overall workforce. Forty-seven percent of state UI claimants since March are Black, far higher than the 25% Black share of the state’s total workforce.[19]

Gender disparities in UI claims also reflect worsening inequities in the workforce. Women make up 58% of Alabama’s UI claimants since March but only 47% of the workforce overall.[20] Women also face greatly increased exposure to the dangers of COVID-19 because they work the majority of health care jobs.[21]

The pandemic’s high economic toll in rural Alabama

The recovery from catastrophically high unemployment has been inequitable by region. Rural counties in Alabama’s Black Belt in particular have lagged behind the state average in returning to pre-pandemic UI claim levels. The populations of these counties are disproportionately Black, and residents continue to face long-term negative consequences both from centuries of wealth extraction and the state’s failure to invest adequately in community well-being.

Black Belt residents also have been economically harmed by unusually high long-term unemployment.[22] Persistently high unemployment resulting from the pandemic simply compounds the region’s existing unemployment and wage disparities.

How did we get here?

Long-term neglect and recent harmful policy changes to the UI system failed Alabama’s workers when they needed the most support. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the state’s failure to maintain and modernize its UI claim infrastructure.[23] Alabama’s UI claim system was unsuited to the unprecedented demand, in part because it operated on outdated technology, as do many other states’ systems. The state’s failure to modernize its computer systems caused long periods of severe financial stress for Alabamians who could afford it the least.

The flawed structure of the state’s UI system is intentional. Alabama’s low-road policy decisions have consistently devalued workers and perpetuated inequality by keeping people insecure about meeting basic needs. The state’s neglect of the claims system is a passive example of undermining worker well-being, but officials also recently have taken active steps that harmed workers.

In 2019, the Legislature and governor enacted a law that lowered the total amount of UI benefits significantly. The law reduced the length of time a worker could claim benefits from 26 weeks to 14, or 19 if a worker could participate in approved job training.[24] It also tied a potential increase of weeks of benefits to reported overall state unemployment rates from the prior quarter.

Besides its harmful impact on workers, the recent UI restriction has two major conceptual flaws. First, the changes fail to account for significant differences in employment opportunities across the state. This increases pressure on people to find work where few or no jobs exist. Second, the lag in reporting the unemployment rate failed to account for the sort of catastrophic economic conditions that COVID-19 delivered. When unemployment rises quickly and sharply, the number of weeks that UI benefits are available does not increase quickly enough to prevent economic pain for unemployed workers.

A UI system that isn’t meeting Alabamians’ needs

Alabama’s UI system has a low payout rate. Though the number of repeated weeks of claims for a single loss of employment has dropped since March 2020, fewer than half of initial claims had been deemed valid and paid out through Nov. 30.[25] This low payout rate shows Alabama is not doing enough to provide UI coverage to people harmed by layoffs.

The state’s failure to pay out claims in a timely manner has compounded the hardship for Alabamians out of work because of COVID-19. And further, the state response has inaccurately assessed the damage that the pandemic has caused to Alabama workers. The state Department of Labor has classified a substantial portion of these UI claims as unrelated to COVID-19.[26] But that characterization is unpersuasive in light of the drastic increase in claims, with the pandemic’s beginning the only major change in workforce conditions.

Lack of broadband access limits opportunities

The COVID-19 shutdown has heightened the impact of Alabama’s “digital divide.” As schools and many workplaces shifted to online activities, workers with lower incomes often found themselves at a double disadvantage. First, their jobs were less likely to be adaptable to remote settings. Second, their households were less likely to have the reliable internet connection and computer equipment required for online learning or work.

Alabama’s lack of broadband internet can limit remote work even for people whose jobs allow it. The Alabama Broadband Accessibility Act defines an “unserved area” as a rural part of the state where internet service falls below the minimum threshold of an average 25 megabits per second for downloading and 3 megabits per second for uploading.[27] And much of Alabama is designated as “unserved” by the state authority that oversees broadband access.[28] Huge swaths of rural Alabama are caught in this gap, including almost all of Greene and Perry counties and much of west Alabama from Fayette and Lamar counties in the north to Choctaw and Clarke counties in the south.[29] Even in relatively urbanized counties like Jefferson, Madison, Montgomery and Shelby, many rural areas lack reliable internet service.[30]

One-time relief payments simply aren’t enough

Relief payments helped individuals and families pay the bills but went away too soon. The quick passage of the CARES Act in late March 2020 provided a lifeline for Alabama families reeling from the shutdown.[31] In the spring/early summer stage, an average of 23% of Alabamians who were not working (including both those who were unemployed and those who are retired) reported relying on the relief payments to help with bills.[32]

In a telling and troubling sign, the percentage of such households declined over the same period.[33] This probably reflects exhaustion of one-time stimulus checks as people used them to meet basic needs. In mid-June, 34% of people who were not working said they used relief funds to pay bills during the past week.[34] This percentage declined to 17% by mid-July.[35]

What should we do now?

Alabama can create a better system for responding to the needs of workers who lose their jobs. Worker-friendly policies create a better, more stable economy for everyone. Alabama can make several changes that would improve conditions for unemployed workers, including strengthening work supports, fixing the UI system and improving implementation of federal COVID-19 relief measures. Specifically:

- Alabama must invest in its UI compensation infrastructure, both human and technological, to improve our ability to get these funds out quickly to unemployed people. Specific changes would include institutionalizing the recent temporary move to 26 or more weeks of UI assistance and permanently repealing the 2019 law cutting available weeks of assistance. In addition, the Alabama Department of Labor should issue guidance to allow people at high risk from COVID-19 to retain UI benefits if they quit a job that is taking insufficient virus precautions.

- The state should stop conditioning receipt of benefits on participation in job training programs. Workers receiving UI benefits already have demonstrated a desire to work and the ability to maintain long-term employment by meeting the minimum earnings and time requirements for UI eligibility. Creating barriers for people who lose their jobs only serves to punish job seekers and burden an already strained state claims system.

- The state should expand the availability of work supports, including training, child care and transportation. To get to work, people first need the ability to get to the workplace. They also need adequate job preparation and reliable care for family members to ensure full participation in the state’s economy.

- Expand high-speed, affordable broadband technology, targeting rural and low-income communities and explicitly addressing racial equity in broadband access.

Federal relief

- Alabama should direct significant federal relief funds to emergency housing and utility assistance. Unemployed Alabama workers are facing hunger, eviction and utility shutoffs in the dead of winter. And Alabamians already pay one of the highest rates for electricity in the South. While federal relief funding is available for emergency housing and utility assistance, the housing assistance is still being processed by the state, and utility assistance ran out in January. CARES Act funding could fill the temporary void in housing assistance and supplement the inadequate federal utility assistance.

- Congress should pass a comprehensive new relief package. Significant numbers of unemployed Alabamians relied on relief payments to meet basic needs early in the recession. That need has not disappeared. Congress’ next relief measure should increase targeted relief payments and reinstate the $600 weekly federal UI boost for eligible workers. The package also should expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and make the Child Tax Credit fully refundable. And it should extend the December 2020 increase to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.

The State of Working Alabama 2021

Footnotes

[1] Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Local Area Unemployment Statistics data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), December 2020.

[2] EPI analysis of BLS Current Employment Statistics, December 2020.

[3] Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown & Shawn Fremstad, “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries,” Center for Economic and Policy Research (April 7, 2020), https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries.

[4] EPI analysis, supra note 1.

[5] Rho, supra note 3.

[6] Alabama Department of Labor, http://www2.labor.alabama.gov/LAUS/LAUSTab.aspx.

[7] Ibid.

[8] EPI analysis, supra note 2.

[9] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, April 23 – July 21, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase1.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Id.

[13] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 2, Aug. 19 – Oct. 26, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase2.

[14] Alabama Department of Labor, “Initial Unemployment Claims for Week Ending 2/6/2021,” https://www.labor.alabama.gov/news_feed/News_Page.aspx?id=318.

[15] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Economy at a Glance,” https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.al.htm.

[16] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Unemployed persons by duration of unemployment” (Feb. 6, 2020), https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t12.htm.

[17] The Century Foundation, “Who Is Getting UI?” (Jan. 24, 2021), https://tcf.org/content/report/unemployment-insurance-data-dashboard.

[18] Alabama Arise calculations based on Alabama Department of Labor, supra note 14.

[19] The Century Foundation, “Who Is Getting UI?,” supra note 17.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity” (Jan. 22, 2020), https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm.

[22] Alabama Department of Labor, “Civilian Labor Force by County – December 2020,” http://www2.labor.alabama.gov/LAUS/clfbycnty.aspx (citing 2019 unemployment data).

[23] Lydia Nusbaum, “State’s system overwhelmed as number of unemployment claims surge,” WSFA 12 News (March 25, 2020), https://www.wsfa.com/2020/03/25/states-system-overwhelmed-number-unemployment-claims-surge.

[24] SB 193, 2019 Regular Session of the Alabama Legislature, https://legiscan.com/AL/bill/SB193/2019.

[25] The Century Foundation, “Unemployment Insurance Data Dashboard” (updated Jan. 24, 2021), https://tcf.org/content/report/unemployment-insurance-data-dashboard (citing Alabama Department of Labor report to U.S. Departments of Treasury and Labor).

[26] See generally Alabama Department of Labor, News, https://labor.alabama.gov/news_feed/News_Page.aspx (linking press releases with individual weekly breakdowns of UI claims caused by COVID-19 and purportedly not caused by COVID-19).

[27] Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs (ADECA), “Alabama Broadband Accessibility Fund Frequently Asked Questions,” https://adeca.alabama.gov/Divisions/energy/broadband/Broadband%20Docs/Frequently%20Asked%20Questions.docx.

[28] ADECA, “Alabama Broadband Eligibility Map – Unserved Areas as of 11/23/2020,” https://adeca.alabama.gov/Divisions/energy/broadband/Broadband Docs/Alabama_Broadband_Eligibility_Map_Unserved_Areas.pdf.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Sharon Parrott, Chad Stone, Chye-Ching Huang, Michael Leachman, Peggy Bailey, Aviva Aron-Dine, Stacy Dean & LaDonna Pavetti, “CARES Act Includes Essential Measures to Respond to Public Health, Economic Crises, But More Will Be Needed,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (March 27, 2020), https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/cares-act-includes-essential-measures-to-respond-to-public-health-economic-crises.

[32] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, April 23 – July 21, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase1.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Week 7 Household Pulse Survey: June 11 – June 16, Employment Table 2, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp7.html.

[35] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Week 12 Household Pulse Survey: July 16 – July 21, Employment Table 2, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp12.html.