Introduction

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Alabama in March 2020, it didn’t just cause massive human suffering and economic disruption. It also revealed suffering and disruption that have long existed and that policymakers have long neglected – or even perpetuated.

COVID-19 has laid bare deep racial inequities in Alabama’s economy and social system that have left our state unprepared to meet the needs of its people in this disaster. As the workers predominantly on the front lines, women and people of color bore the brunt of the economic meltdown. They also simultaneously have suffered greater exposure to the virus that caused it.

Alabama has a weak safety net for struggling families and an approach to economic growth that all too often leaves workers underprotected and underpaid. This ongoing policy legacy has exacerbated the damage that the virus has wreaked on the state’s working people.

In The State of Working Alabama 2021, Alabama Arise explores COVID-19’s significant and negative impacts on the state’s workforce. We also look ahead to outline a state and federal policy agenda for repairing the damage – not by repeating the policy mistakes of the past, but by charting a new path toward a more equitable economy marked by broadly shared prosperity.

Report navigation

You can read all seven sections of the report by clicking on the corresponding section’s icon at the bottom of this page. The executive summary of each section and of some of the report’s key policy recommendations is below, as are the report acknowledgments.

You can click any image in this report to enlarge it. To download a printable version of the executive summary, click here. To read our news release on the report, click here.

COVID-19 and Alabama’s policy legacy

COVID-19 struck Alabama’s families and communities hard, and the toll has been especially high for Alabamians of color. The virus and the shutdown exacerbated massive underlying disparities in health care, economic security and access to essential resources that policymakers have long ignored. And they revealed how our neglect of the common good – through low wages for average working people, low taxes for rich people and racially discriminatory policies for our entire state – has left many Alabamians unable to weather a crisis and hindered the entire state’s ability to rebound.

- The “essential workers” hailed as pandemic heroes often lack the basic protections of a living wage, health insurance, paid sick leave and family medical leave.

- Alabama’s fundamental state policies have been unequal by design, including its explicitly racist 1901 constitution. Right-to-work laws, preemption and other measures have blocked efforts to protect and support working families.

- Working Alabamians without health coverage are at even greater risk during the pandemic due to extension of broad liability protection to corporations and other entities for damages related to COVID-19.

Labor market

The COVID-19 recession hit vulnerable Alabama workers hard and fast, disproportionately affecting women and workers of color.

- Alabamians working in already low-wage industries suffered immediate and severe job losses, which fell hardest on women and people of color. By December 2020 – nine months into the pandemic – Alabama still had a net loss of 35,400 jobs, a 1.7% decline from pre-pandemic levels. The hardest hit industry was leisure and hospitality, including entertainment and food service establishments where workers were already struggling.

- Unemployment insurance (UI), designed for just such a moment, was inadequate and insufficient to meet working people’s needs because of Alabama’s policy choices. In 2019, the state cut compensable weeks of UI and tied benefit extensions to longer-term statewide unemployment rates. This framework is wholly unsuited to catastrophe response.

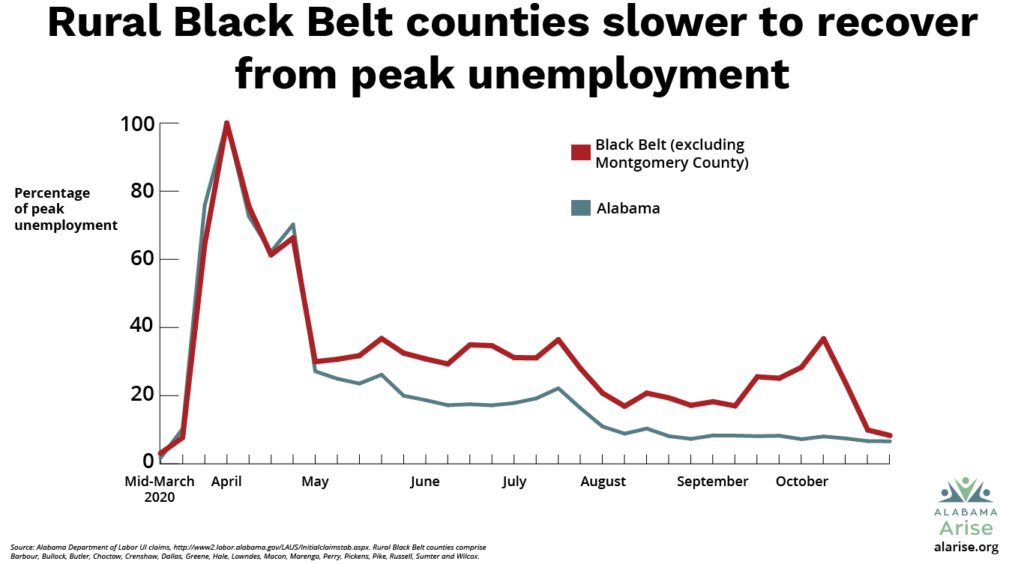

- COVID-19 has caused disproportionate unemployment for Black people and women. Economically disadvantaged counties in the Black Belt and other parts of Alabama also have lagged behind in unemployment recovery.

- Alabama’s lack of investment in updated claim processing systems has caused harmful lags in paying out UI claims. The state’s failure to modernize claim processing damages the well-being of people who drive the economy. Modernization would be quick, efficient and helpful to Alabamians.

- Alabama’s failure to invest in rural broadband made it even more difficult for people in large swaths of the state to work or attend school remotely. This “digital divide” is depriving many Alabamians of opportunities to learn and earn.

Recommendations

- Establish a state minimum wage significantly higher than the current federal minimum wage. The pandemic recession’s impacts have fallen hardest on people who were already struggling to make ends meet.

- Roll back the harmful 2019 cuts to UI benefits. Those changes reflected a shortsighted approach to UI and demonstrated counterproductive hostility to working people who have lost their jobs.

- Invest in support structures to allow communities that are at an economic disadvantage to participate fully in the workforce.

- Create a reliable, modernized claims system capable of handling a crisis with claims significantly exceeding peak UI claims resulting from the pandemic.

- Expand high-speed, affordable broadband technology, targeting rural and low-income communities and explicitly addressing racial equity in broadband access.

Front-line workers

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Alabamians have come to recognize a new category of “heroes.” Front-line workers in grocery stores, hospitals, pharmacies and other settings perform necessary tasks to keep our communities functioning during the public health emergency.

- Front-line workers, who face greater exposure to COVID-19 than the general population, are disproportionately women and people of color. Because of barriers to health care, Black and Hispanic/Latinx workers also are more likely to have underlying conditions that worsen COVID-19 outcomes. State and national policy failures on the pandemic response, especially inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), are more likely to hit front-line workers the hardest.

- Thousands of working Alabamians were left out of paid sick days protections. Between half and three-quarters of all Alabamians were left out of the paid sick days protections in the federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act. This omission places entire workplaces at risk of exposure to the virus.

Recommendations

- Implement hazard pay for front-line workers during the pandemic.

- Guarantee permanent paid sick leave for all working Alabamians, regardless of employer size, so that no one has to choose between earning a paycheck and going to work sick.

- Expand Medicaid so front-line workers have affordable, timely access to treatment for health risks that worsen COVID-19 outcomes.

Health care

While the COVID-19 pandemic has slammed all segments of our economy and society in one way or another, health care is where most of these effects converge.

- Alabama had the 11th highest COVID-19 death rate among states in mid-February 2021. That means a higher share of Alabamians have died from the virus than in most other parts of the country. By mid-February, Alabama’s COVID-19 deaths in less than a year had surpassed 9,200, far more than the number of Alabamians who died in World War II and all subsequent wars (8,215).

- COVID-19 has exposed a shameful legacy of unequal access to health care. In the early days of the pandemic, Black Alabamians accounted for as many as 55.2% of Alabama’s daily COVID-19 deaths, more than double their 26.8% share of the population.

- The pandemic widened racial/ethnic disparities in health coverage. Before the pandemic, 62.2% of Alabama’s white workers had health insurance through their jobs. The same was true for only 46.4% of Black workers and just 35.5% of Hispanic/Latinx workers. Early in the COVID-19 shutdown, Hispanic/Latinx Alabamians reported lack of insurance at nearly three times the rate of white residents.

- COVID-19’s disparate impact on communities of color has opened a new conversation about health equity. A smart recovery will take a broader approach to building a healthy workforce by adopting policies that address food security, adequate housing and other social determinants of health.

Recommendations

- Expand Medicaid to cover more than 300,000 Alabama adults with low incomes. This health coverage expansion would facilitate COVID-19 testing, treatment and vaccination; allow working people to stay healthier and more productive; and strengthen Alabama’s health care system, especially rural hospitals. The Legislature’s eagerness to provide businesses with immunity against COVID-19 liability claims only makes the need for worker protections like health coverage more urgent.

- Make reducing health disparities a state priority. Alabama should adopt a rigorous program of data collection across state agencies to identify disparities in health outcomes related to race/ethnicity, income and geography. This effort should engage research universities and state health agencies in developing and implementing a strategic plan to reduce targeted health disparities and give all Alabamians a chance to thrive.

Hunger

Job and income losses during the pandemic have contributed to widespread hunger in Alabama.

- Too many people struggled to keep food on the table during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the spring/early summer stage of the pandemic (April through July 2020), 12% of all Alabama families and 13% of Alabama families with children either sometimes or often didn’t have enough food to eat.

- Hunger was much more widespread in communities of color. Nearly 21% of Black residents and 19% of Hispanic/Latinx residents said they didn’t have enough food.

- Proven safety net programs played a critical role in alleviating hunger. Food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) was key to helping hundreds of thousands of Alabamians keep food on the table during this recession. And emergency food and child nutrition services eased hardship among Alabama’s children as schools closed or went virtual.

Recommendations

- Alabama lawmakers should abandon efforts to slash the state’s safety net. Past proposals to restrict SNAP and other safety net programs would have made the recent hunger and hardship in Alabama even more dire.

- Congress should move quickly to institutionalize recently increased UI, child nutrition and SNAP assistance. Hunger has grown during the pandemic, reaching crisis proportions. Boosts to UI, child nutrition and SNAP benefits have been essential tools to help struggling Alabamians meet their basic needs.

- Congress should provide additional cash assistance, similar to the earlier relief payments, targeted specifically to families with low incomes. Targeted relief should include a fully refundable Child Tax Credit and an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Relief payments were a significant source of cash for food and other basic needs during early stages of the recession. And federal assistance will remain important as struggling Alabamians rebuild in the aftermath of the COVID-19 recession.

Housing

Thousands of Alabamians face potential eviction and homelessness because of inadequate response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated recession.

- Alabamians can’t afford adequate housing. Many Alabamians in the workforce face housing insecurity because low wages burden renters heavily. Even basic apartments are out of reach for low-wage workers everywhere in the state.

- COVID-19 has caused increased housing insecurity. Alabamians face high risk of eviction during the COVID-19 pandemic, largely because of insufficient state-level protections.

- Housing insecurity is significantly racially disparate. Black and Hispanic/Latinx Alabamians face far higher risk of eviction for inability to pay rent. Long-standing inequities in the state’s economic structure have caused Black and Hispanic/Latinx communities to have fewer resources in reserve for weathering hard times.

Recommendations

- Fund the Alabama Housing Trust Fund (AHTF). Lawmakers in 2012 created the AHTF as a vehicle to promote safe, affordable homes for people with extremely low incomes. A small increase in the recording fee for mortgages could boost the AHTF and significantly increase housing availability. This would facilitate more construction of affordable homes in the Black Belt and other rural areas.

- Renew the state moratorium on evictions. Job losses amid the pandemic recession are causing evictions that otherwise would not have happened. The current limited federal moratorium fails to cover all Alabamians and requires administrative hurdles that leave holes in the system. By restricting evictions during the pandemic to reasons directly related to public safety, the governor could protect thousands of Alabamians from higher risk of COVID-19 transmission and from devastating long-term economic consequences.

Acknowledgments

This Alabama Arise report was made possible by a generous grant from EARN in the South. The findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of Arise and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of EARN in the South.

The report’s authors are Arise policy director Jim Carnes, policy analysts Carol Gundlach and Dev Wakeley, visiting fellow Allan Freyer and intern Resha Swanson. Arise communications director Chris Sanders was the report’s primary editor. Arise communications associate Matt Okarmus designed the charts and graphs and provided online design for the report. Bixler Creative designed the report logo and provided print design for the executive summary. Other report editors and contributors included Arise executive director Robyn Hyden and organizer Mike Nicholson.

Special thanks to Adelante Alabama Worker Center for producing a companion report to The State of Working Alabama 2021 and to Marie-Pier Frigon at New Mexico Voices for Children for providing guidance on chart and graph design.

The State of Working Alabama 2021