MEDICAID BASICS

What you need to know …

- Medicaid is a joint federal/state program providing health coverage for certain categories of people with low incomes and limited resources.

- More than 1.2 million Alabamians qualify for Medicaid coverage.

- Medicaid payments support doctors’ offices, hospitals, clinics and nursing homes that serve all Alabamians.

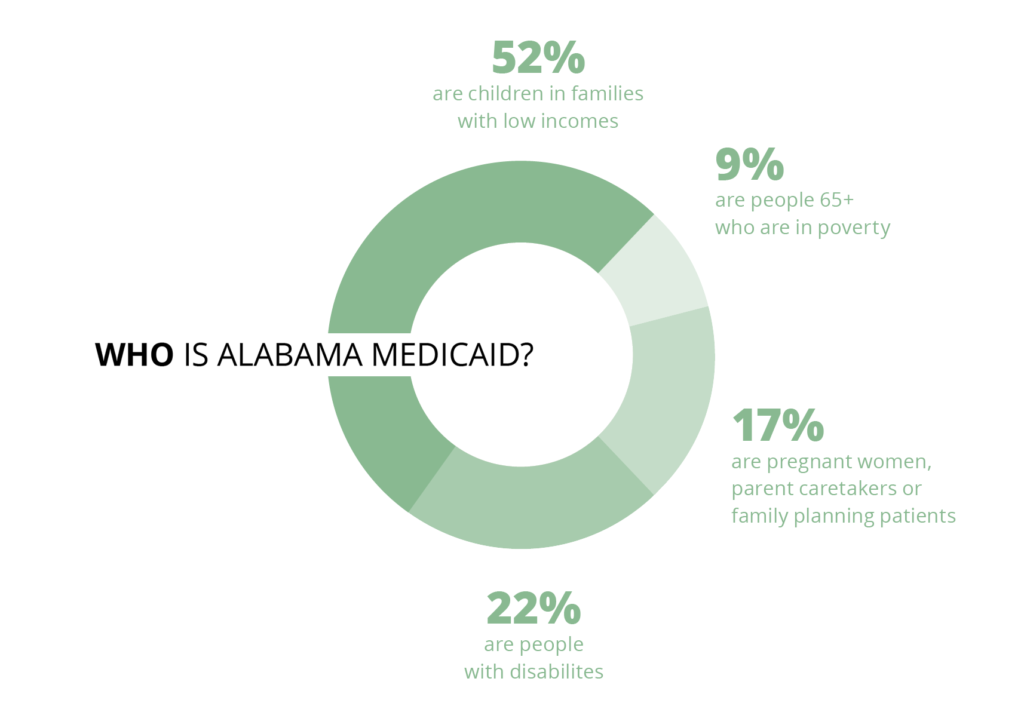

- Children make up more than half of Alabama Medicaid beneficiaries.

- Medicaid also provides essential coverage for seniors, pregnant women, and people with disabilities.

- Alabama Medicaid’s eligibility limits are among the nation’s most restrictive.

Medicaid is the backbone of our health care system

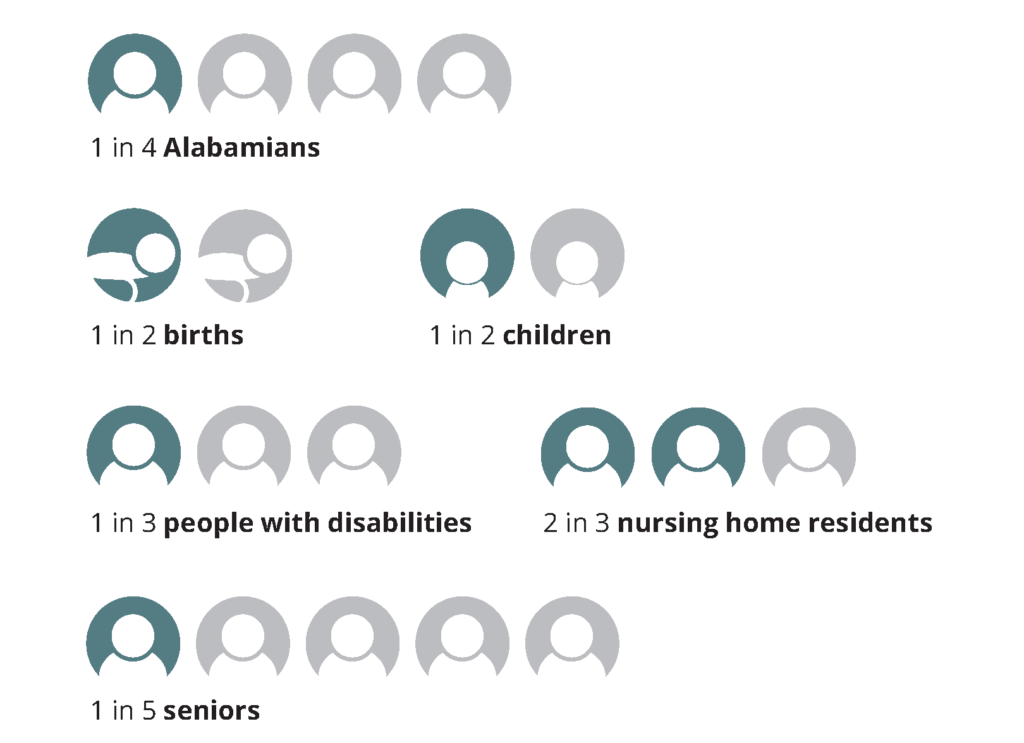

More than 1.2 million Alabamians, or 25% of our state’s population, qualified for Medicaid coverage in fiscal year 2017. Looking closer, that’s:

Medicaid pumps $7 billion in federal and state money into our health care system every year. Without Medicaid funding, many of the doctors’ offices, clinics, hospitals and other medical facilities that all Alabamians depend on would have to cut services or close.

Medicaid pumps $7 billion in federal and state money into our health care system every year. Without Medicaid funding, many of the doctors’ offices, clinics, hospitals and other medical facilities that all Alabamians depend on would have to cut services or close.

SPOTLIGHT

Meet Silvia Hernandez

To get her son the speech therapy he needed a few years ago, Silvia Hernandez of Fort Payne had to drive him two hours each way to the recommended therapist in Birmingham. Her top priority was her son’s health care, but Silvia saw firsthand the hurdles of time and resources that some parents in her area would have trouble getting over.

When Silvia encounters a problem, she goes to work — this time literally. Today, she is the owner of Go Play Therapy, a practice she built and opened in response to the provider shortage in her area. Go Play specializes in occupational, physical and speech therapy for children up to age 18. There are two Go Play locations, in Fort Payne and Centre.

Hernandez estimates 90% of her clients have Medicaid.

“If Medicaid didn’t exist, we’d have to shut our doors,” Silvia says. She adds that extending Medicaid coverage to adults with low incomes — not just their children — would help even more people gain access to the care they need. As a business owner, she sees another advantage to Medicaid expansion: It would allow her to expand her therapy office and hire additional employees.

Who is Alabama Medicaid?

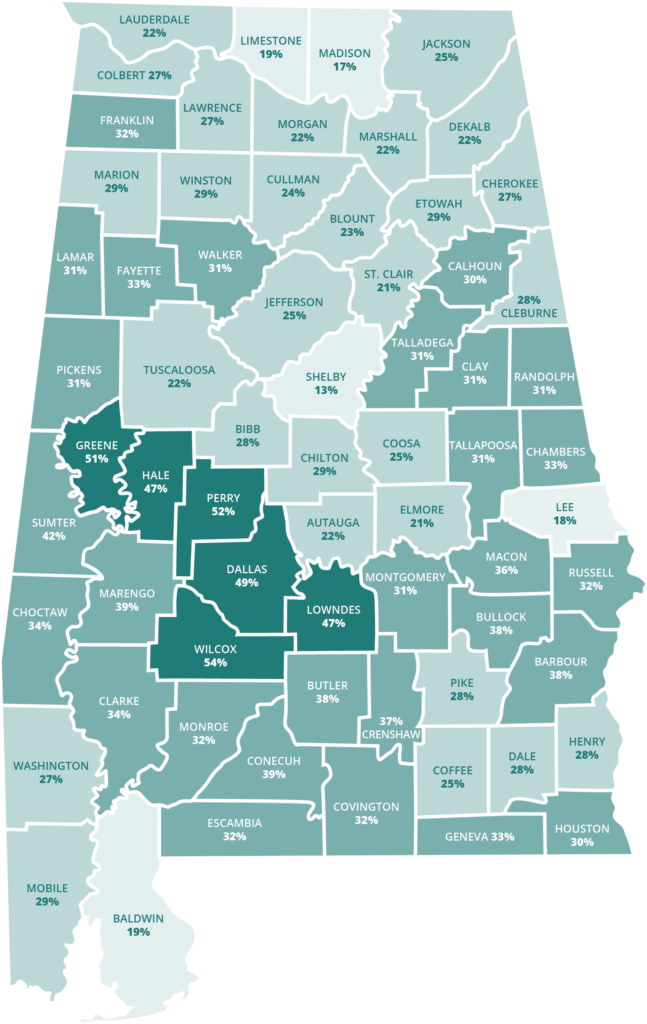

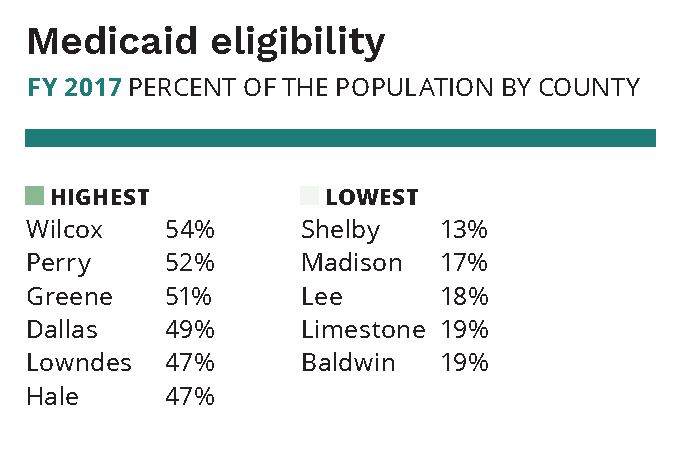

Alabamians in every county qualify for Medicaid

About one in every six Alabamians lives in poverty. For children, the rate is nearly one in four. Even Alabama’s most prosperous counties have significant numbers of households living below or near the poverty level. That means Medicaid is a lifeline for families across the entire state.

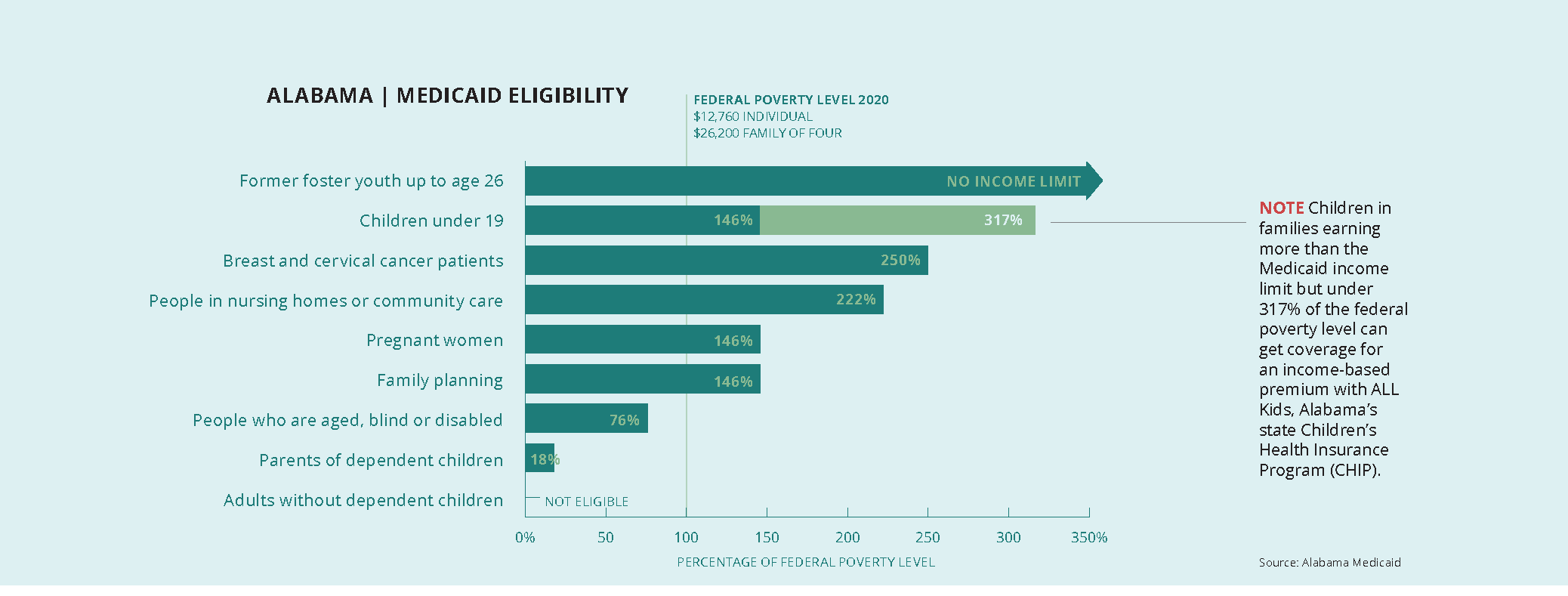

How do people qualify for Medicaid coverage in Alabama?

When an individual or family applies for Medicaid, a number of factors determine whether they’re eligible and which program would best serve their needs. Age, income, family size and certain health conditions like pregnancy or disability all play a part.

The household income limit for a particular program is expressed as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL) — often in shortened form, such as “146% of poverty.” The higher the percentage, the more income an individual or family may have and still qualify for Medicaid.

The income limits for Alabama Medicaid’s eligibility groups are shown below. In 2020, the FPL was $12,760 for an individual and $26,200 for a family of four.

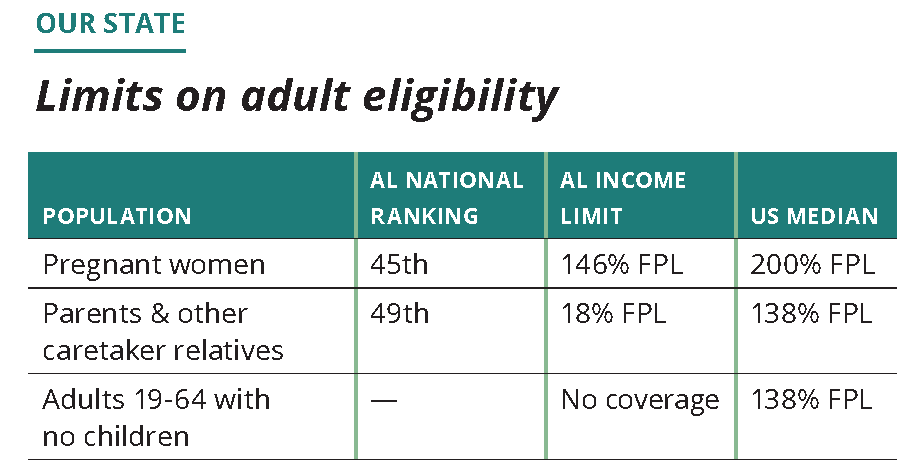

How does Alabama’s Medicaid eligibility compare?

Children’s health coverage has long been a point of pride for Alabama. We were the first state to launch a Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) after Congress created that option in 1997. While our family income limit for children in Medicaid is the third lowest in the country at 146% FPL, ALL Kids covers children above the Medicaid limit up to 317% FPL. That puts Alabama among the top 10 states for CHIP eligibility. For working-age adults, however, Alabama Medicaid’s income limits tell another, far more troubling story.

National ranking: 49th

For adults without children or a disability, we’re one of 14 states that offer no Medicaid coverage. And only Texas makes it harder than Alabama for parents of dependent children to get Medicaid coverage.

How does Medicaid funding work?

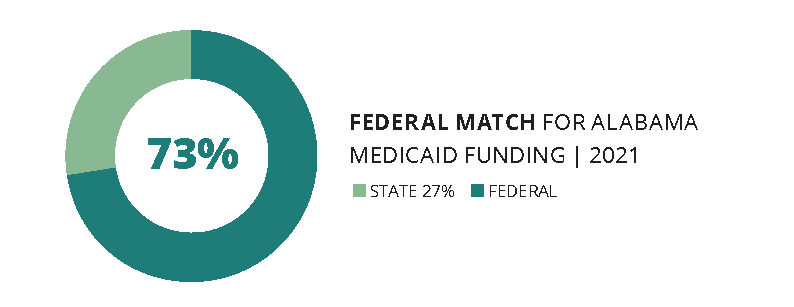

The federal government pays at least half of each state’s Medicaid costs. The percentage (called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage, or FMAP) is set annually through a complicated formula based on per capita (or per person) income. The lower the state’s per capita income, the higher the FMAP, up to a maximum 83%. Alabama’s FMAP for FY 2021 will be 72.58%. This means we get roughly $7 in federal money for every $3 Alabama pays for Medicaid. Alabama Medicaid’s total annual budget is about $7 billion.

State money for Medicaid comes from a number of sources, including the General Fund (GF), special trust funds, and transfer payments from public hospitals. Because the revenues earmarked for the GF come from minor taxes, fees and interest payments that grow slowly, Medicaid and other GF services remain permanently shortchanged.

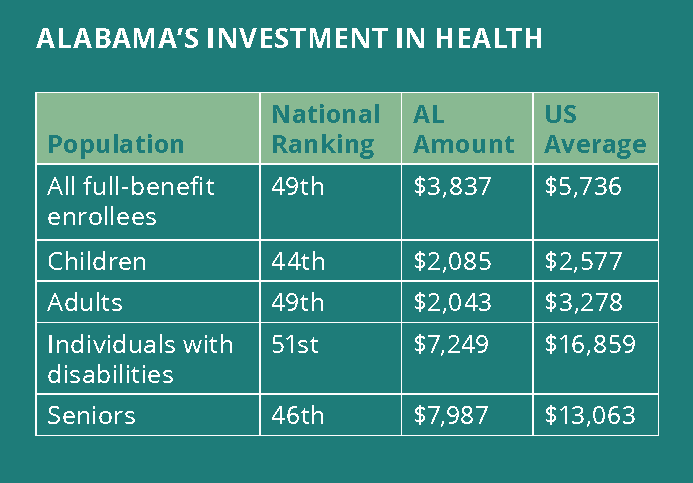

How does Alabama’s Medicaid investment compare?

One simple way to compare Medicaid programs across states (and the District of Columbia) is to rank their spending per enrollee in major Medicaid eligibility groups. Spending is only one factor in the delivery of care, but it does indicate the investment that the state is willing to make in the health of residents with low incomes. Here’s how Alabama measures up on that count:

What services does Medicaid cover?

To qualify for federal funding, state Medicaid programs must cover:

- Well-child check-ups, known as EPSDT (Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment, including dental services), for all Medicaid-eligible children under age 21. Because most Medicaid beneficiaries (also known as members) are children, EPSDT is the most wide-reaching Medicaid service.

- Inpatient and outpatient hospital care.

- Doctor services.

- Laboratory and X-ray services.

- Skilled nursing.

- Family planning services.

- Pregnancy-related services.

- Ambulance services.

Alabama is one of only three states where Medicaid does not cover any dental care for adults.

The federal government also identifies optional Medicaid services that states may offer. Alabama offers only a few of these, including adult prescription drug coverage, adult prosthetics and community-based hospice care. In addition, Alabama has waivers, or special permission, to offer home- and community-based long-term care and regionally based coordinated primary care.

IN FOCUS

Children with special health care needs

Alabama Medicaid and ALL Kids together cover more than 105,000 children with special health care needs. These children are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions. They require services tailored to these needs.

The Medicaid portion of this population includes more than 21,000 children who received Supplemental Security Income (SSI) in 2018. A child receiving SSI has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, including emotional or learning problems, that results in marked and severe functional limitations and has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months.

SPOTLIGHT

Meet Mattisa Moorer and Kerstin Sanders

Like many teenagers, Kerstin Sanders enjoys movies, being out in the crowd, chilling out and sleeping in. Cerebral palsy, Dandy Walker Syndrome, epilepsy, scoliosis and restrictive lung disease are facts of her life, but they aren’t her life.

Kerstin is a treasure to anyone who takes the time and effort to know her, says her mother, Mattisa Moorer.

As Kerstin ages, her care becomes more complex. For example, multiple surgeries and procedures have made it necessary to change her feeding tube more frequently. Medicaid pays for most of the medications and supplies that Kerstin needs every month.

“It’s been a life-saver,” Mattisa says.

The Lowndes County single mom realized she would need to be an advocate for her daughter when Kerstin entered Head Start. At first, the school’s special education coordinator listened carefully and designed a plan that allowed Mattisa to be a classroom aide. But a change of administration caused the plan to unravel.

“I saw that I need to continuously advocate for Kerstin’s inclusion and, at middle school, her access,” Mattisa says. That calling now has expanded to include working part-time as a parent consultant with Family Voices of Alabama and serving as a consumer representative with her local Alabama Coordinated Health Network (ACHN).

While patient advocacy has come with struggles — waiting lists, paperwork, hard-to-obtain information — Mattisa values her successes. She considers the camaraderie of others in similar situations to be one of her biggest wins.