Quality, affordable child care is essential for families seeking to escape poverty and participate in employment, education and training activities. The Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), a federally funded program that subsidizes care for low and moderate-income parents of young children, provides critical funding for affordable child care.

In Alabama, CCDBG funds are administered by the Department of Human Resources (DHR). The agency also administers the closely related Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance program. Congress reauthorized the CCDBG in 2014 and included significant quality improvement goals for states. In 2018, Congress provided a historic CCDBG funding increase, allowing DHR to serve more Alabama children in higher-quality settings.

The importance of federal child care funding in Alabama

Federal CCDBG funding has increased, allowing Alabama to expand access to child care and improve quality. In 2017, Alabama received $53.2 million in discretionary CCDBG funds from Congress. The 2018 federal funding increase grew Alabama’s CCDBG grant to $93.9 million – a 76.5% increase.

Alabama faces deadlines to obligate and expend federal funds. Like other states, Alabama must obligate 2018 federal CCDBG dollars by Sept. 30, 2019, and expend those dollars by Sept. 30, 2020. Alabama is on track to meet the obligation and spending deadlines and anticipates no problem obligating or spending the grant.[1]

The additional CCDBG money was enormously important for child care in Alabama. The state does not provide any child care funding, except for the required match for the federal Child Care Entitlement to States grant, and does not use federal TANF funds for child care.[2] Alabama includes state-appropriated funds for pre-K education as a portion of its TANF maintenance of effort (MOE) obligation. But these funds were not, and could not be, supplanted with additional federal dollars.

How Alabama is using new CCDBG funding

Alabama used its new federal dollars to make investments that benefit children, families, workers and communities. The funding increase allowed Alabama to expand child care access and come into compliance with the 2014 reauthorization law. The state also made numerous improvements to its subsidized child care system.

According to officials and contractors with DHR,[1] the state has:

1. Eliminated the waiting list for child care slots. In 2017, Alabama provided child care subsidies to slightly more than 38,000 children. In April 2019, 42,000 children received subsidies, and slots remain available for more children.[3] The state’s regional Child Care Management Agencies, which determine eligibility for subsidies and help enroll children, are actively using social media and word of mouth to recruit new children.[1] Eligible families now can access care within one week of application.[1]

2. Increased initial subsidy eligibility from 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) to 130%. That income is about $28,000 a year for a family of three.

3. Eliminated all copays that were less than $18 per month. This essentially eliminated copays for all families with income below the FPL.[1]

4. Increased provider rates twice.[1] Alabama now reimburses providers beginning at 70% of fair market rates. That is a significant increase over the prior reimbursement rates ranging from 14% to 40% of fair market rates. While this does not reach the federally recommended base level of 75%, it is a major improvement over prior years.

5. Allowed training and technical assistance providers, such as Childcare Resources in Birmingham and the Family Guidance Center in Montgomery, to offer training to workers at faith-based exempt facilities, schools, YMCAs and other exempt centers.[1] These providers also were able to increase bonuses paid to workers who participate in on-the-job training.

6. Increased scholarships for child care workers studying early childhood education, including scholarships up to the bachelor’s level.

7. Increased child care for recently unemployed parents to 90 days (up from 30 days) while they seek new jobs. DHR is planning a program that would include unemployed parents in workforce development so they will not lose child care after the 90-day period ends.

8. Expanded Help Me Grow, a referral and case-management system for children ages birth through 8, including more referrals to child care and to other health and developmental services, such as obesity prevention.[1]

9. Expanded the First Five program, which teaches parents and child care workers best practices for promoting social and emotional development of young children.

Disparities and barriers to child care access in Alabama

Alabama has significant racial and ethnic disparities in who receives child care assistance. In 2016 (the latest data available), 79% of children receiving child care subsidies were African American.[4] This is significantly higher than the national rate of 39%, as reported by the Center on Law and Social Policy (CLASP).[5] Approximately 29.5% of Alabama children are African American, and their poverty rate is more than twice that for whites. This is a major driver of the racial disparity in receipt of child care assistance.

Alabama is among the bottom five states in the share of eligible Hispanic children receiving child care subsidies, CLASP found. The state provides child care assistance to only 1% of potentially eligible Hispanic children.[5]

Providers suggested language barriers, fear of immigration enforcement, lack of knowledge of the availability of child care subsidies, and reliance on care by family members contribute to low participation among Hispanic families. Past outreach efforts by community-based Hispanic organizations have been unsuccessful. But efforts to encourage Hispanic parents to apply for family care subsidies are expanding and may help increase participation.[1]

Who would benefit from greater eligibility for subsidized child care?

More Alabama children are now eligible for subsidies, but there is room for further growth. Federal law sets the maximum income for receipt of a child care subsidy at 85% of a state’s median family income (MFI). At this level, 258,662 Alabama children were income-eligible for subsidized child care in 2016, CLASP reports.[5]

Like most states, Alabama sets eligibility for subsidized child care below the federal maximum. Prior to the receipt of new federal funds, Alabama set eligibility at 100% FPL. But after the new funds became available, Alabama raised eligibility to 130% FPL.

Based on that standard, 139,950 Alabama children are now eligible for subsidies, according to CLASP. If Alabama increased the subsidy eligibility standard to 85% MFI, an additional 118,712 children would become eligible for a subsidy.

In April 2019, Alabama provided child care subsidies to approximately 42,000 children, or 35% of kids who are income-eligible at 130% FPL. This is a significant increase from both 2016, when 32,651 children received subsidies, and 2017, when 38,025 children were served.[6]

While more slots are available to serve children beyond the current 42,000, federal funding is still not enough to serve all children in the state eligible at 130% FPL, according to DHR.[1] Absent additional federal funding or new state funding for child care, another increase in the eligibility standard is unlikely.

Affordable child care helps families make ends meet

Most Alabama families have a hard time meeting basic needs, including child care. Children in Alabama whose family income is less than 130% FPL are eligible for subsidized child care. (For a family of three, 130% FPL is $27,729 annually.)

Nowhere in Alabama does the cost of a modest standard of living fall below the cap for subsidized child care. The Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator[7] estimates that the annual cost of living for two adults and one child in Huntsville is $63,360, including $430 per month for child care. In Selma, meanwhile, the annual estimated cost of living for the same family size is $56,695, including $387 per month for child care. And in Dothan, the annual estimated cost is $61,005, including $414 per month for child care.

The geography of child care access in Alabama

The share of young children Alabama’s child care market can serve is inadequate and varies widely by geography. No congressional district in Alabama has enough child care slots to serve every child under age 6 in the district, according to the Center for American Progress.[8] (See the table below.)

The lack of slots is particularly severe in some districts in north and central Alabama. The 4th Congressional District has only enough licensed child care slots to serve 20% of potentially eligible children. And the neighboring 6th Congressional District has only enough slots to serve 19% of potentially eligible children.

Both the 4th and 6th Districts have a disproportionate number of unlicensed, faith-based centers, a challenge discussed below.[1] Large areas of both districts are also economic suburbs of Birmingham, which is largely in the 7th Congressional District. Interviews with providers suggested residents of these counties might prefer child care facilities near their jobs rather than their homes.[1]

Providers interviewed suggested several changes that could increase the availability of care. These include increased subsidies for family day care homes and kinship care and higher reimbursement rates for center care, especially at initial certification.

State child care administrators also agree that more providers are needed, particularly in areas near U.S. 80, which runs through the 2nd, 3rd and 7th Congressional Districts in Alabama’s Black Belt.[1] They believe the state has a critical need for day care homes, centers offering non-traditional hours, centers that can provide infant and toddler care, and providers who can care for children with special needs.

Availability of licensed child care by Alabama congressional district

| Alabama congressional district |

Children under 6 |

Percentage of children under 6 in poverty |

Number of licensed child care slots |

Share of young children that market can serve |

| 1 |

51,900 |

23% |

16,316 |

31% |

| 2 |

49,400 |

23% |

19,928 |

40% |

| 3 |

49,700 |

21% |

14,077 |

28% |

| 4 |

48,600 |

28% |

9,676 |

20% |

| 5 |

49,000 |

22% |

15,100 |

31% |

| 6 |

52,000 |

10% |

9,828 |

19% |

| 7 |

49,900 |

34% |

20,600 |

41% |

The child care shortage in rural Alabama

Alabama has a shortage of group and family child care homes, and this shortage is getting worse. Ninety-five percent of children are now served in child care centers, while only 3% are served in child care homes. And the number of child care homes continues to decline as providers retire.

This is a serious problem in rural counties, particularly in the Black Belt. In many such areas, the number of children needing care is too small and too isolated to support larger centers, and children could be better served in homes with three to 12 children. Rural areas also would benefit from an expansion of subsidized relative care, which is available in all 67 counties but not widely known.[1]

Alabama’s child care licensure deadline

Until a recent change in state law, Alabama exempted religiously affiliated providers from licensure. In 2017, 53% of child care facilities were licensed, while 42% were unlicensed due to religious affiliation.[9] (The other 5% were exempt from licensure for other reasons.)

In 2018, the Alabama Legislature passed HB 76, which required facilities receiving state or federal dollars to be licensed by Aug. 1, 2019. But as of June 2019, nearly 250 faith-affiliated centers, out of a total of 834, had not yet been licensed.

Both the state and technical assistance providers expressed concern that these facilities might not achieve licensure by the deadline and thereby might become ineligible for subsidies. This could result in a loss of slots for subsidized children – or a loss of entire facilities.

The need for quality improvements and new technology

Alabama has a tiered Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) in place. But there is a lack of participation by centers, especially at the higher tiers. This appears to be because increases to provider rate reimbursements per tier are not sufficient to cover the cost of the service improvement.

Interviewees cited the need for increases in reimbursement rates and incentives for quality improvements. They also said more training incentives for center employees and aggressive outreach to providers are needed, along with greater consumer understanding of the importance of the QRIS.[1]

The 2014 CCDBG reauthorization requires extensive reporting of information on the Alabama DHR website. DHR’s computer system is well over 20 years old, creating service delivery problems for many programs they operate. So updating the system will be challenging and expensive, particularly in light of Alabama’s chronic underfunding of human services.

New criminal background checks required by the 2014 reauthorization pose a similar technology problem. These checks are a significant expense: $45 to $50 per background check for more than 15,000 child care facility employees. Data incompatibility between the National Crime Information Center and the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency has led Alabama to request a waiver of this mandate. The state is seeking bids from vendors for this service, but as with the state’s computer system, the cost is expected to be considerable.

A lingering challenge: low pay for child care workers

Low wages for child care workers, most of whom do not earn a living wage, is a serious problem. Many child care center employees are themselves eligible for a subsidy for their own children. A key quality improvement lies in education and training for child care workers, and Alabama has committed considerable resources to training and education subsidies up to the bachelor’s level.

But low wages in traditional child care drive many of the best educated and trained teachers to apply for jobs in K-12 schools, where wages are much higher and benefits, including health insurance and retirement, are much better. Technical assistance providers stressed that salaries and benefits for child care employees needed to reflect those of early childhood teachers in public schools, both for equity and retention of newly trained workers.

Conclusion

Maintenance of federal CCDBG funding at the 2018 level is critical for continued progress in the provision of child care for low- and moderate-income children in Alabama. Increased funding would allow Alabama to expand the number of children who receive assistance by increasing income eligibility to 85% of median family income. It also would allow Alabama to increase per-child subsidies to programs. And that would improve the incomes of child care teachers and the retention of well-qualified and educated teachers.

Footnotes

[1] Interviews conducted by the report author May 24, 2019, through June 4, 2019, with Kathy Camp, program director, Family Guidance Center; Bernard Houston, administrator of child care services and workforce development, DHR; Candice Keller, program manager for subsidy, DHR; Gail Piggott, executive director, Alabama Partnership for Children; Walter White, executive director, Family Guidance Center; and Joan Wright, executive director, Childcare Resources

[2] ACF/HHS, FY 2017 Federal TANF & State MOE Financial Data

[3] Alabama Department of Human Resources, 2017 Annual Report and April 2019 Monthly Statistical Report

[4] ACF/HHS Office of Child Care, FY 2016 Final Data, Table 12a-Average Monthly Percent of Children in Care by Race and Ethnicity

[5] Rebecca Ullrich, Stephanie Schmit & Ruth Cosse, “Inequitable Access to Child Care Subsidies,” Center on Law and Social Policy, April 2019

[6] Alabama Department of Human Resources, Annual Report 2016 and Annual Report 2017

[7] Economic Policy Institute, Family Budget Calculator

[8] Center for American Progress Early Childhood News, “Child Care Supply by Congressional District,” April 10, 2019

[9] ACF/HHS Child Care and Development Fund, Preliminary Data Tables, FY 2017

References

Alabama Department of Human Resources, Annual Statistical Reports, 2017 and 2018

Alabama Department of Human Resources, “Child Care Fact Sheet,” Oct. 1, 2018

Alabama Department of Human Resources, FY 2019-2021 Alabama CCDF State Plan

Alabama Department of Human Resources, State of Alabama Provider Rate Chart, Oct. 1, 2018

Patti Banghart, Carlise King, Anne Partika, and Victoria Perkins, “State Policies for Assessing Access: Analysis of 2016-2018 Child Care Development Plans,” The Early Childhood Data Collaborative, March 2018

Center on Law and Social Policy, “Budget Deal Includes Unprecedented Investment in Child Care,” February 2018

Nina Chien, “Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2015,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS, January 2019

Hannah Matthews, Karen Schulman, Julie Vogtman, Christine Johnson-Staub, and Helen Blank, “Implementing the Child Care and Development Block Grant Reauthorization: A Guide for States,” Center on Law and Social Policy and National Women’s Law Center, June 2017

National Women’s Law Center, “Child Care and Development Fund Plans FY 2016-2018: State Waivers and Corrective Actions,” August 2016

Douglas Rice, Stephanie Schmit, and Hannah Matthews, “Child Care and Housing: Big Expenses with Too Little Help Available,” Center on Law and Social Policy, April 29, 2019

Rebecca Ullrich, Stephanie Schmit & Ruth Cosse, “Inequitable Access to Child Care Subsidies,” Center on Law and Social Policy, April 2019

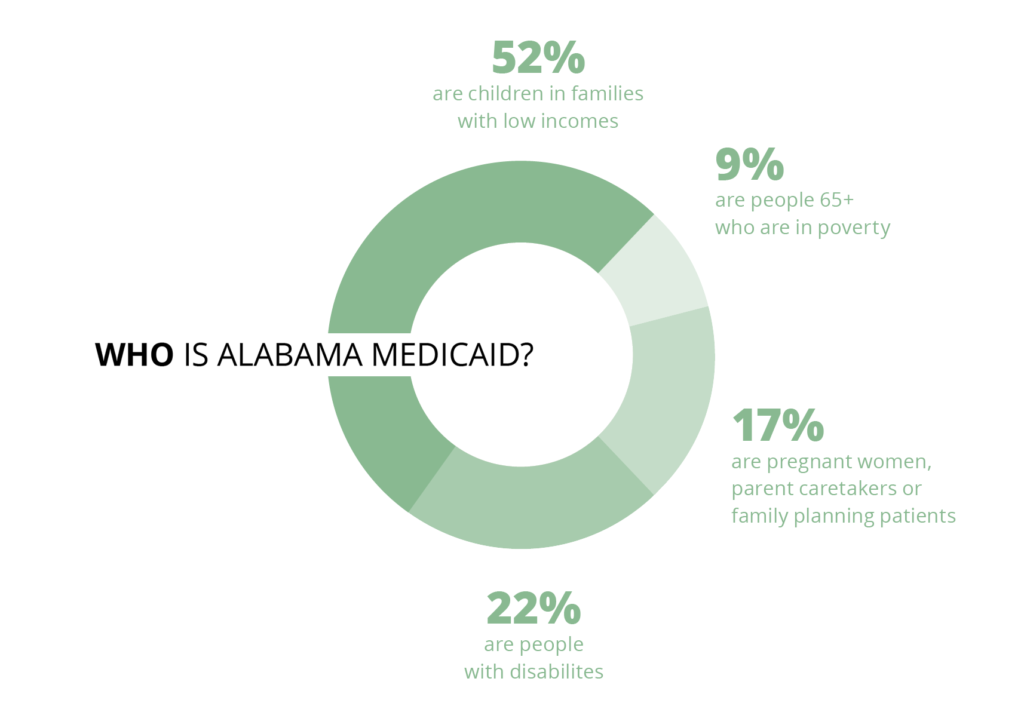

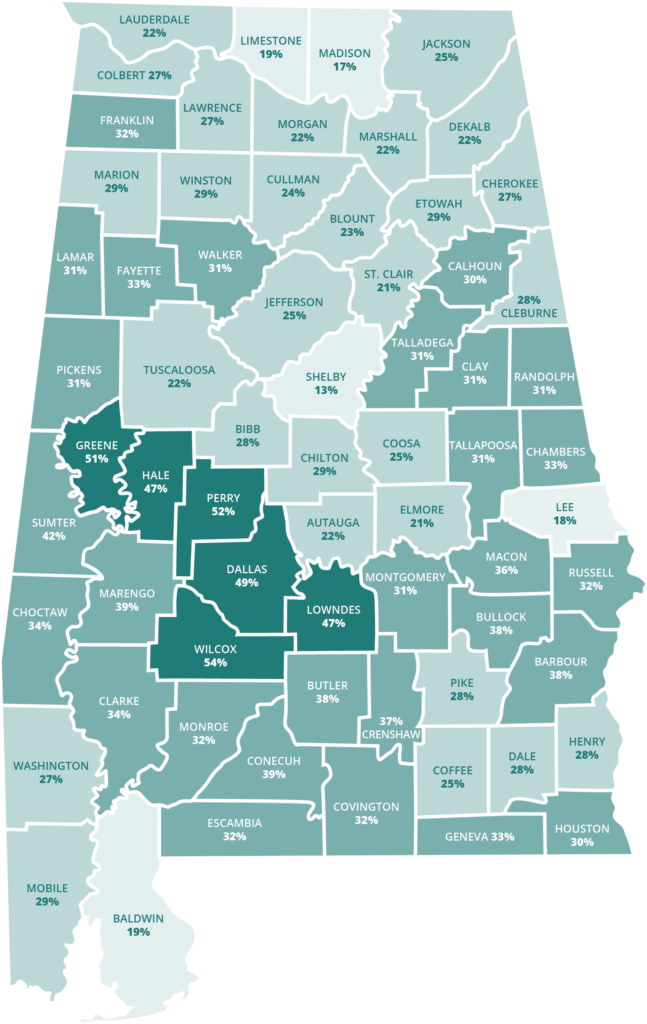

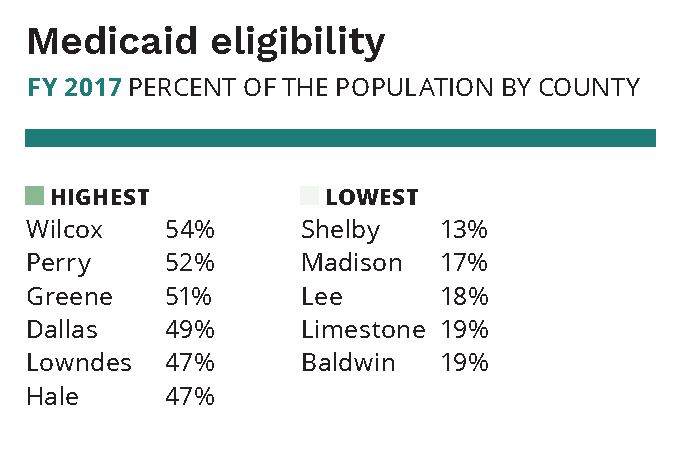

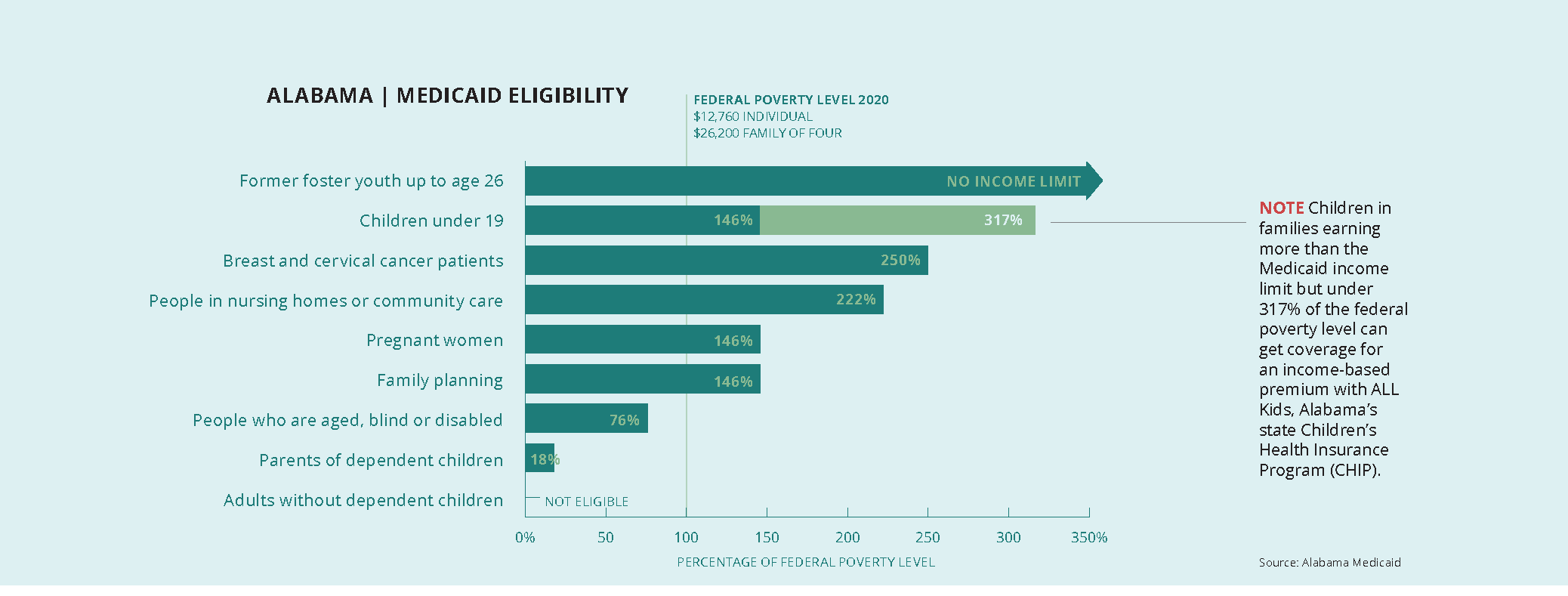

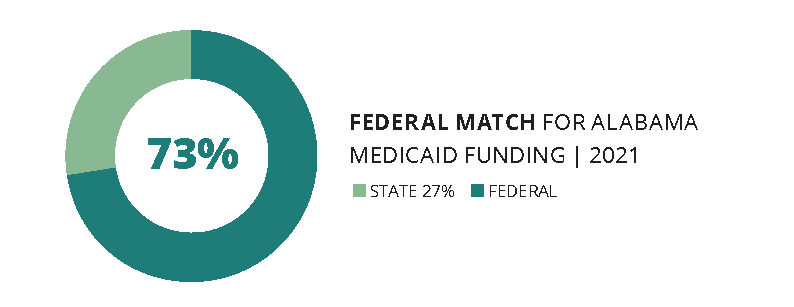

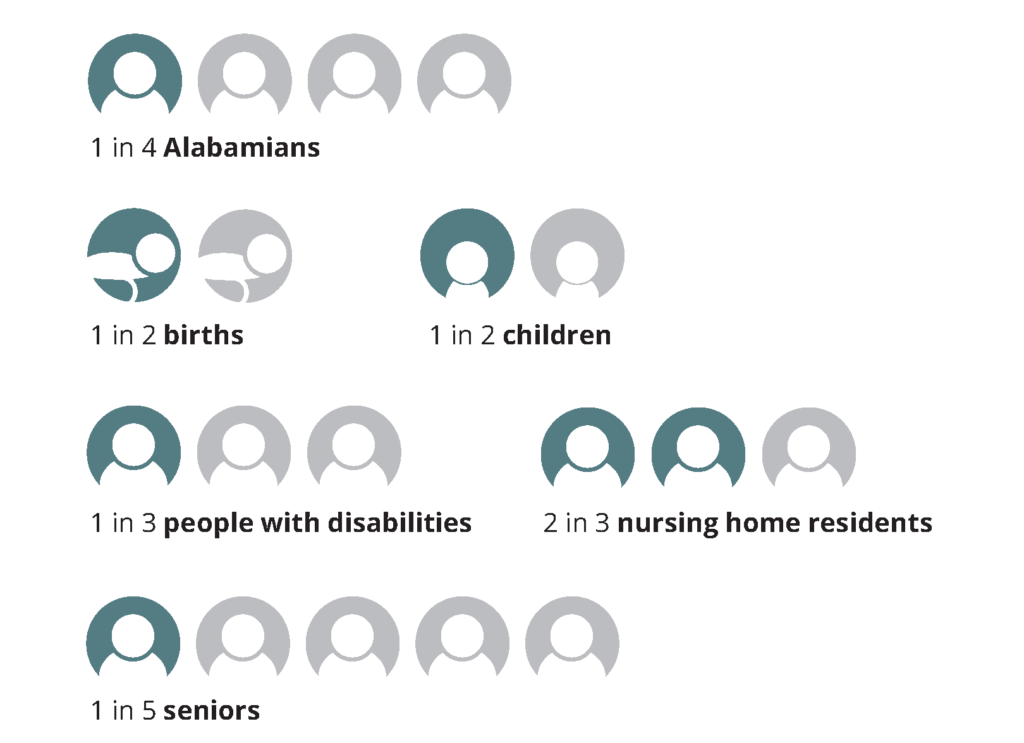

Medicaid pumps $7 billion in federal and state money into our health care system every year. Without Medicaid funding, many of the doctors’ offices, clinics, hospitals and other medical facilities that all Alabamians depend on would have to cut services or close.

Medicaid pumps $7 billion in federal and state money into our health care system every year. Without Medicaid funding, many of the doctors’ offices, clinics, hospitals and other medical facilities that all Alabamians depend on would have to cut services or close.