Alabamians are living through hard times right now. Thousands of people are sick. Many more are scared or out of work. Uncertainty is everywhere amid a pandemic with no clear timetable or end game.

As more businesses close or cut back, as more people lose income, and as fewer of us go to the stores where we normally shop, state tax revenues are falling. That endangers funding for education, public health and other core services at a time when we need them most.

A state Senate committee Tuesday approved a smaller General Fund (GF) budget than the one Gov. Kay Ivey initially proposed. But that budget’s revenue assumptions may be too optimistic, and many lawmakers acknowledge they may need to revisit it this summer or fall as the pandemic’s financial toll becomes clearer. In the meantime, the ongoing public health emergency is compounding structural problems that have plagued Alabama for decades.

How Alabama should strengthen its tax system

The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated economic freefall are not the root cause of Alabama’s chronic underfunding of public services or the fundamental failures of its tax system. But this crisis is exposing and exacerbating those shortcomings. And it is illustrating the need for progressive tax changes that would equip our state to endure both this downturn and future recessions.

Alabama should enact these changes to raise revenue for vital services and make life better for struggling families:

- Eliminate the regressive, and expensive, state income tax deduction for federal income taxes. About 80% of the $782 million deduction’s benefit flows to the top 20% of households.

- Increase income tax brackets so the highest-paid 25% of taxpayers have a higher tax rate than people in the lower and middle brackets do. Alabama’s top income tax rate kicks in at just $3,000 of taxable income.

- Impose a temporary income surtax on millionaires during the financial crisis.

- Adopt combined reporting to prevent corporate tax avoidance while rejecting proposals, such as moving to a single sales factor formula, that would reduce taxes for large corporations.

- Eliminate the state sales tax on groceries and replace that revenue by making progressive improvements to our income tax system. Alabama is one of only three states with no tax break on groceries.

- Apply sales and use taxes to more professional services and digital goods and services like music downloads and video streaming services.

- Institute or increase sales and excise taxes on unhealthy items like tobacco, vaping products or sugary soft drinks. The state could dedicate this money to Medicaid and other health care services.

Lessons from the past: How the last recession devastated Alabama’s finances

Alabama has two major revenue sources for public services that rise and fall with the economy. One is the income tax, which is earmarked (or dedicated) solely for K-12 teacher salaries. Sales and use taxes, which largely go toward education but also fund some other services, are the other. (Use taxes apply to online and mail-order purchases.) Most GF revenue sources grow slowly even in good times.

To understand this downturn’s potential impact, we should look back to the last recession, which struck Alabama in 2009. Both the Education Trust Fund (ETF) and GF were prorated as revenues plummeted during the Great Recession. Proration is an across-the-board funding cut when revenues fall short of expectations.

ETF revenues went down 11.8%, or $702 million, between 2008 and 2009. GF revenues for services like courts, Medicaid, public safety and veterans’ assistance fell by 13.9%, or $250 million.

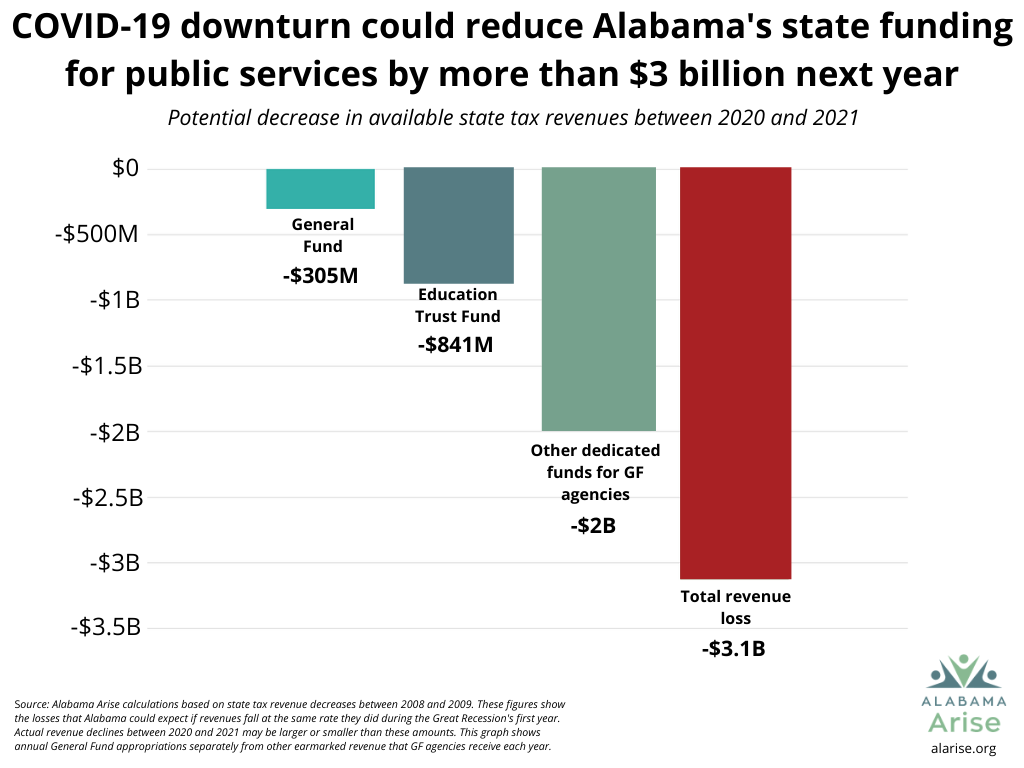

The ETF could lose $841 million in state money next year if revenues decline at the same rate as in 2009. This would be equivalent to $1,160 per student in public K-12 schools, or 20% of all state K-12 funding. It’s also more than this year’s state allocations to the University of Alabama and Auburn University systems combined.

Meanwhile, the GF could lose $305 million if this downturn matches the Great Recession. That would be equivalent to 2020 GF funding for the Department of Human Resources (DHR), mental health, public health and senior services combined.

This loss also doesn’t include other dedicated funds for GF agencies like child welfare, mental health and veterans’ services. If these earmarked funds dropped by 13.9%, as the GF did in 2009, Alabama would need another $2 billion to avoid cuts. Altogether, the total funding loss to education, health care and other services would exceed $3 billion.

Rainy day funds and federal relief will help, but they aren’t a lasting solution

Thankfully, Alabama has three revenue sources to help avoid or reduce service cuts, at least temporarily. Lawmakers have established two rainy day funds – essentially lines of credit – within the Alabama Trust Fund that the governor can tap to address major budget shortfalls. The ETF also has a reserve fund called the Budget Stabilization Fund, which can be tapped if revenues aren’t enough to cover budgeted expenses.

The governor can authorize withdrawal of no more than 14% total of the prior year’s education spending from a combination of the Budget Stabilization Fund and the ETF Rainy Day Fund. That amounts to around $997.6 million. And the state can withdraw 10% of prior-year spending for other services from the GF Rainy Day Fund, which comes to $219.2 million.

Between the two budgets, the governor could withdraw $1.2 billion from rainy day accounts. But to maintain current funding levels, Alabama still would need another $1.8 billion if this downturn matches the Great Recession.

Alabama expects about $1.8 billion in federal relief as a result of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. This one-time relief could get the state through 2021 by a hair – if federal officials allow it. The U.S. Treasury is restricting the extent to which states can use these funds to plug budget shortfalls. Cumulative shortfalls in Alabama and other states from 2020-22 could top $650 billion, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates.

COVID-19’s budgetary threats don’t end there. Local governments also will need relief, and this fiscal crisis may be even worse than 2009. If a 2020 recession spirals into a depression, we will be facing some very dark days without new tax revenue to make them brighter.

The path to stronger, more inclusive budget and tax policies for Alabama

Alabama could respond to these steep revenue losses with harmful cuts to education, mental health care, public health and other critical needs. Or the state could make the wiser choice of raising sustainable new revenue to invest in the common good.

Our partners at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy said it best: “For states facing catastrophic revenue declines, asking more of taxpayers with a clear ability to pay is far preferable to cutting state budgets, which would lead to mass layoffs, steep cuts in public services, and a downward spiral in the economy.”

Year after year, Alabama legislators have built a series of bare-bones budgets on one-time funds and temporary federal aid. They’ve refused to modernize our state’s upside-down tax system by making it more progressive and more fair for struggling families. And they’ve refused to ask large corporations and wealthy people who can afford to pay more to contribute their fair share to support the common good.

There’s a better way. The progressive tax changes we propose would protect education, health care and other services from devastating cuts during the COVID-19 recession. They also would allow our state to expand Medicaid and ensure all Alabamians can get the health care they need to survive and thrive, both during this pandemic and in the long recovery ahead. If we want a brighter future for Alabama, we need to invest in it now.