The 1901 Alabama Constitution is overreaching, poorly written and harmful to many of the people it governs. Its authors intentionally disenfranchised people of color, women and people with low incomes in an effort to silence them politically. The document also created barriers to governance for local elected officials. More than a century later, these barriers still limit opportunities for change at the local level today.

Alabama voters will have the opportunity on Nov. 8, 2022, to adopt a recompiled state constitution. This amendment would authorize changes such as removal of racist language and illegal provisions that have since been repealed. Arise is urging Alabamians to vote “Yes” on the recompilation in November. These changes wouldn’t address all of the problems with the state constitution. But they would move Alabama, and our constitution, in the right direction.

A shameful start

In his opening remarks, the president of the 1901 constitutional convention declared a major goal was “within the limits imposed by the federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state.” The resulting document effectively removed the voting rights of African Americans and poor white people. By concentrating power in the hands of a few special interests, it allowed wealthy landowners to keep their property taxes low at the expense of school funding for low-income children.

Federal courts have overturned most of the discriminatory provisions, but the shameful evidence of this legacy persists in our constitution. This concentration of power remains an obstacle to effective local government. The constitution similarly hinders state officials from modernizing our tax system to serve Alabama’s current economic realities. And the document limits lawmakers’ ability to change policies that perpetuate the harmful and racist objectives overtly codified in 1901.

The home rule question

In Alabama, counties must seek constitutional amendments to conduct many routine functions of local government, known as home rule. At 977 amendments and counting, the Alabama constitution is 12 times longer than the average state constitution and 40 times longer than the U.S. Constitution. Because many amendments require a statewide vote, and because legislators can override many proposed local actions, the rights and privileges of people in one county are often granted or denied by residents of other counties that would be unaffected by such changes.

One example came in 2015, when legislators from across Alabama blocked Birmingham’s attempt to institute a $10.10 minimum wage. The law effectively prevented cities from setting minimum wages responsive to their local needs – even though Alabama has set no state minimum wage at all. An earlier example came in 2004, when Trussville officials sought to raise local property taxes that fund their public schools. Because of tax-related provisions in the state constitution, the move required statewide approval of a constitutional amendment. The measure won 68% support from Trussville voters, but 55% of Alabama voters rejected the amendment. People living hundreds of miles away from Trussville thus helped prevent the city from improving funding for its local schools.

Both instances demonstrate state lawmakers’ carefully preserved ability to undermine the autonomy and political authority of local communities. Those restrictions are especially egregious when a mostly white Legislature limits the authority of Black local officials.

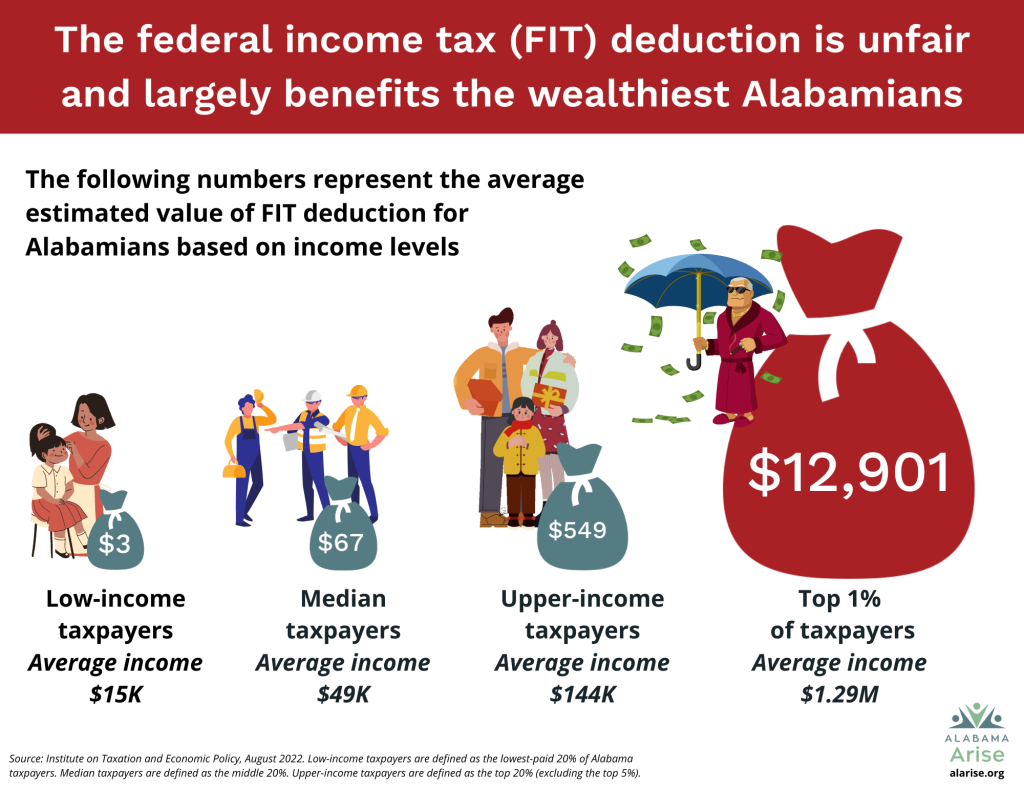

Our antiquated tax system

The 1901 constitution perpetuates a tax structure that favors wealthy people, overtaxes people with low incomes and fails to provide adequate funding for vital services. The state property tax rate, for example, has not increased since the constitution was written. The document requires a voter referendum to raise local property taxes to support schools. Amendments in the 1970s restricted the assessment of taxable property value, which further limited funding for public schools. And for decades, the now-illegal poll tax ensured only prosperous white voters had a decisive voice in elections.

Some prosperous districts in Alabama spend more than twice as much per pupil as high-poverty districts. Because our state and average local property tax rates are among the nation’s lowest, our education system is one of the most poorly funded. When a 1933 amendment established the state income tax, it was designed to affect only the wealthiest residents. But because income brackets for these rates have changed very little in 75 years, most Alabamians now pay at the top rate. As a result, Alabama’s income tax is among the highest in the nation for families at the poverty line. Similarly, those with the highest incomes no longer pay a fair share. Writing tax policies into the constitution made these policies difficult to modernize in response to inflation and changing needs.

The sales tax is perhaps the most regressive tax. It takes nearly eight times the share of income for the state’s lowest earners as for its wealthiest families. Sales taxes rise and fall with the economy, like income taxes but unlike property taxes. As a result, our state education budget, which relies heavily on income and sales taxes, is at risk of sharp cuts when the economy slows.

Barriers to meeting Alabama’s basic needs

The constitution limits Alabama’s ability to provide needed services for struggling families. For example, a 1952 amendment prohibits use of state gas tax revenue for public transportation. As a result, inadequate transportation keeps thousands of Alabamians from meeting basic needs, such as getting to work, going to the doctor or traveling to the grocery store. Every year, Alabama frustratingly leaves millions of federal matching dollars on the table because we can’t put up the state share.

Our antiquated tax system places a straitjacket on state funding for other vital services, too, such as health care and child care. Most states earmark, or set aside for use, a little more than 20% of their tax revenues. But Alabama earmarks more than 80% of our revenues. That leaves the governor and the Legislature little flexibility to match available resources to pressing needs. Alabamians suffer when earmarking impedes an opportunity to maximize federal matching funds or increase health coverage.

Advocates for a new Alabama constitution have been divided for decades over how to best achieve their goals. Some want to hold a convention at which elected delegates would craft a new constitution all at once, subject to voter approval. Others have favored a gradual, article-by-article rewrite. Lawmakers have taken the latter approach in recent years, revising several articles but avoiding meaningful changes to tax policy or home rule.

A step forward: the recompiled state constitution

Efforts to modernize and improve the state constitution continue despite the challenges. In 2020, Alabama voters overwhelmingly approved an amendment authorizing the Legislative Services Agency to clean up and consolidate the constitution and remove explicitly racist content and illegal provisions that have since been repealed. Examples of deleted racist language include references to separate schools for Black and white children and prohibition of interracial marriages. The Legislature approved the proposed revisions in the 2022 regular session without a dissenting vote.

On Nov. 8, 2022, Alabamians will vote on whether to authorize those changes by adopting the recompiled state constitution. Arise recommends voting “Yes” on the recompilation, which will appear on the ballot as the Constitution of Alabama of 2022.

Alabama Arise urges a ‘Yes’ vote on the recompiled state constitution

Alabama Arise is committed to recognizing, teaching about and repairing the damage that state lawmakers perpetrated for generations through codifying racism and racist practices. Racist language and the harmful provisions flowing from it have no place in our state’s most important legal document. That is why we urge Alabamians to vote “Yes” on the recompiled state constitution on Nov. 8, 2022.

The recompilation will appear on the 2022 general election ballot as the Constitution of Alabama of 2022. Here is the full text that voters will see: