Where are we now?

While the COVID-19 pandemic has slammed all segments of Alabama’s economy and society in one way or another, the health care industry is where most of these effects converge. By the end of 2020, more than 350,000 Alabamians had tested positive or were considered likely positive for the virus, 72% of them in the working-age range of 18 to 64.[1] More than 4,500 Alabamians had died of COVID-19 by Christmas.[2]

The pandemic’s toll has continued to mount in 2021. Alabama had the 11th highest COVID-19 death rate among states in mid-February 2021.[3] That means a higher share of Alabamians have died from the virus than in most other parts of the country. By mid-February, Alabama’s COVID-19 deaths in less than a year had surpassed 9,200,[4] far more than the number of Alabamians who died in World War II and all subsequent wars.[5] The average risk of death from the virus remains low, but:

- The risk is not distributed evenly across age, racial/ethnic and economic groups.

- Complications can be long-lasting and debilitating.

- Everyone with a positive diagnosis has a new preexisting condition. This could affect their access to health coverage if Congress seeks to remove Affordable Care Act protections in the future.

Pandemic’s burden heavier on women, Black Alabamians

As COVID-19 swept across the country in spring 2020, the virus’s disproportionate impact on Black Americans quickly became apparent in emergency rooms, ICUs and death data, where that information was available.[6] When the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) began daily COVID-19 data reporting in early April, Black people accounted for 52.1% of confirmed deaths,[7] while comprising only 26.6% of the population. Americans of color are more likely to have chronic health problems than their white counterparts for numerous reasons. These factors include barriers to health care, transportation, adequate nutrition and other basic necessities.

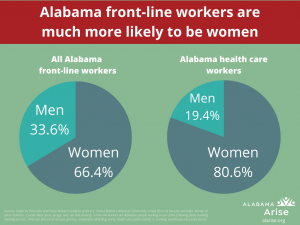

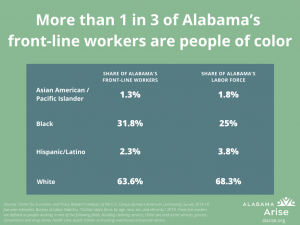

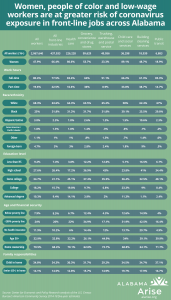

Other sections of this report highlight Alabama’s disproportionate reliance on women and people of color in various jobs that pose high risk of coronavirus exposure. Health care workers are a special case in this regard. For these workers, contact with infected individuals is not just a risk but a job requirement. And the Alabamians meeting this challenge are overwhelmingly women, at 80.6% of the health care workforce.[8] Black people make up 31.2% of Alabama’s health care workers, as compared to their 25% share of the state workforce overall.[9]

As providers of costly health services, doctors’ offices, clinics, hospitals and nursing homes are businesses, too. They can’t operate without keeping their personnel safe, functional and paid, without essential supplies on hand, and without keeping the doors open – challenges for any business during a pandemic. While many retail, manufacturing and hospitality businesses have seen their customer bases shrink dramatically during the shutdown, many health care providers have experienced waves of increased demand. Alabama’s failure to expand Medicaid to cover adults with low incomes has placed economic strain on providers serving these patients.

How did we get here?

The lifeblood of all this activity is the health insurance coverage that, for most Alabamians, pays much of the bill. While 55.9% of Alabama workers had employer-sponsored coverage in 2019, this overall rate masked wide disparity by race and ethnicity.[10] Among white workers, 62.2% had health insurance through their jobs, while the same was true for only 46.4% of Black workers and just 35.5% of Hispanic/Latinx workers in our state.[11]

Prior to COVID-19, almost 300,000 Alabamians with low incomes were caught in the state’s health coverage gap.[12] They earn too much to qualify for Medicaid under the state’s stringent eligibility limits but too little to afford private plans. Working-age Alabama parents are generally ineligible if their income is above 18% of the federal poverty line – just $3,960 a year for a family of three.[13] And virtually all Alabama adults without children are ineligible regardless of income.[14]

COVID-19 deepens coverage disparities by race, income

Working Alabamians make up the majority of those in the coverage gap, along with people who are caring for family members, going to school or awaiting disability determinations.[15] And the racial coverage disparity is stark: Forty-nine percent of uninsured Alabamians with low incomes are people of color, even though people of color make up just one-third of the state’s population.[16]

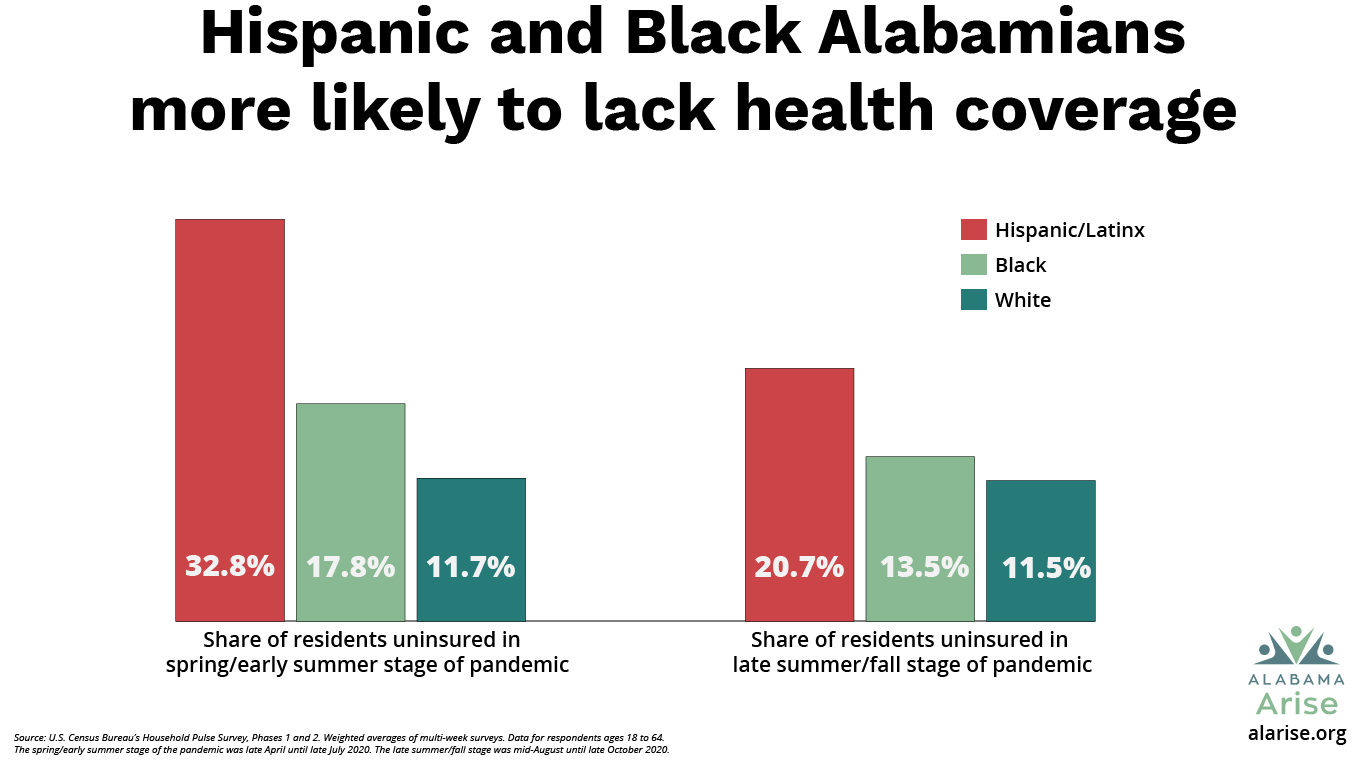

Job losses during the pandemic have reinforced racial disparities in health coverage. The initial impact during spring and early summer fell particularly hard on working-age Hispanic/Latinx Alabamians, who reported being uninsured at a rate of 30.3%. That was nearly twice the rate for Black people (15.7%) and nearly three times the rate for white people (10.3%).[17] Despite some gains, by late summer and early fall, Hispanic/Latinx Alabamians still reported being uninsured at twice the rate for white people.[18]

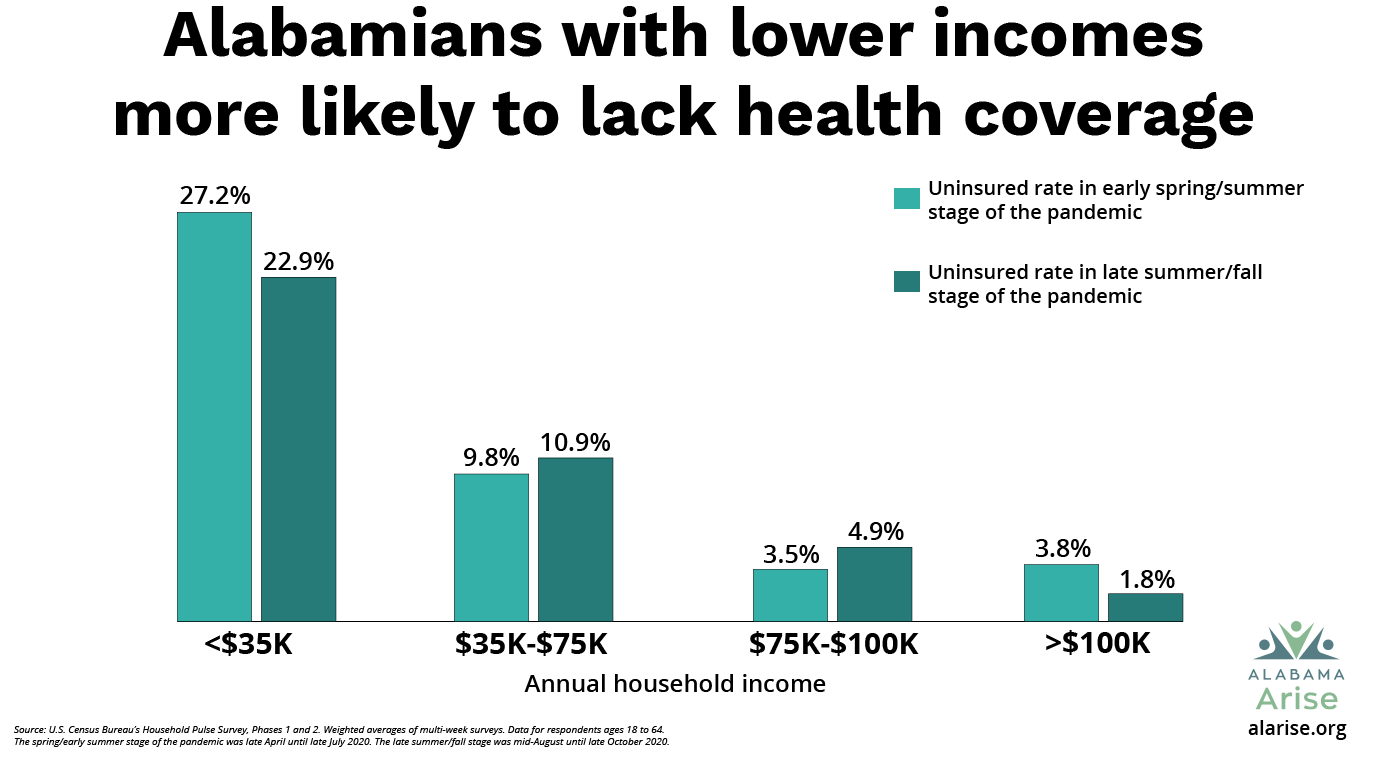

An analysis of uninsured rates by income level reveals even more striking disparities. During both the spring/early summer and late summer/fall stages of the pandemic, uninsured rates were highest by far for workers earning below $35,000 a year, and the rates decreased consistently as income increased.[19] In the first stage, Alabamians earning below $35,000 reported an uninsured rate of 27.2%, while those earning $100,000 and above showed a rate of just 3.8%.[20] In the second stage, those rates dropped to 22.9% and 1.8%, respectively.[21] Broadly speaking, the higher the income, the more likely workers are to have either employer-based health insurance or the means to purchase private plans.

Expand Medicaid to save lives, advance racial equity

The most direct solution to these coverage gaps is Medicaid expansion. A 2019 UAB study estimated that expansion would enroll more than 346,000 Alabamians – most of the eligible uninsured, plus some people who are paying for insurance they can’t afford.[22] Alabama’s high uninsured rate for low-wage workers underscores the fact that Medicaid expansion is a pro-worker policy. And given the disproportionate share of people of color in the coverage gap, expanding Medicaid is the biggest step Alabama can take to advance racial equity in our health care system.

It’s been hard to break through with numerous policy solutions to remove Alabama’s barriers to health care. For example, Alabama Medicaid was unwilling to cover most telehealth services for people who lack reliable transportation – until the COVID-19 shutdown made remote services imperative. And though nutritional supports like vouchers for healthy groceries are available through Medicaid in some states, they’re not in Alabama.

Alabama also has refused to remove the 4% state sales tax on groceries,[23] which would make nutritious food more affordable and give all state households the equivalent of two weeks of free groceries every year. And most notably, Alabama has yet to join 38 other states (plus the District of Columbia) in covering working people with low incomes through Medicaid expansion,[24] a policy change that would directly address Alabama’s racial/ethnic health disparities.

As noted elsewhere in this report, many Alabama lawmakers have expressed more interest in protecting businesses from COVID-19 liability claims than in protecting working people from health risks and economic hardship. A balanced approach to corporate immunity would include expanding health coverage and workers’ compensation for the working Alabamians who have enabled companies to stay in business during the pandemic.

What should we do now?

Just as a hurricane or earthquake tests the strength of buildings and provides a template for improving durability, a health crisis like COVID-19 offers clear lessons for strengthening worker health protections and services. The following measures would help Alabama be better prepared for the next pandemic. They also would promote a healthier workforce and an economy in which everyone has an equal opportunity to thrive. Alabama should:

- Provide health coverage for adults with low incomes by expanding Medicaid. This single step would facilitate more COVID-19 testing, treatment and vaccination; increase worker health and productivity; and strengthen Alabama’s health care system, especially rural hospitals. Lawmakers’ rush to immunize businesses against pandemic-related claims only makes the need for worker protections like health coverage more urgent.

- Expand use of telehealth services by means of universal broadband access and provider incentives.

- Identify and address health disparities. Adopt a rigorous data collection program across state agencies to identify health outcome disparities related to race/ethnicity, income and geography. Engage research universities and state health agencies in developing and implementing a strategic plan for reducing targeted health disparities.

- Support community health. Develop and implement a strategic plan for linking underserved communities with health care by means of community health workers. Alabama is one of just three states that have not defined a role for community health workers in the state health care system, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy. Our state’s failure to act is depriving underserved communities not only of improved health services and outcomes but also job creation and economic development.

- Promote community-based participatory research to increase chronic and infectious disease awareness, preventive behaviors and health equity.

In focus

Powering up for recovery: The vaccine trust factor

If we’re smart, the links between social justice and health that the pandemic is exposing will improve our chances for beating it. All eyes are on vaccine distribution. Immunizing Alabama against COVID-19 is a matter not just of coordinating vaccine delivery and covering costs, but also building trust.

Alabama had mixed success with the adoption of protective equipment and protocols to mitigate COVID-19’s spread during most of 2020. Similar resistance to accepting the vaccine could delay our state’s economic recovery even further.

Understanding the relative influences of skepticism and lack of information and access on vaccine participation warrants further research. But Alabama’s public health legacy – and living memory – adds a painful dimension to this issue. In the home state of the racist and deadly Tuskegee syphilis experiment,[25] public health officials have a long way to go to win the full confidence of communities long betrayed.[26]

Nationally, Black Americans are significantly less likely than white people to get the annual flu vaccine.[27] This fact raises the stakes for a new vaccination campaign. A 2020 CDC study found that Hispanic/Latinx adults had lower flu vaccine uptake than any other racial/ethnic group.[28] People with disabilities also have shown lower flu vaccine participation.[29] And a recent study found that unemployed Americans were less likely to receive the flu vaccine and also less likely to say they would accept a COVID-19 vaccine.[30]

We have to make sure – and make clear – that Alabama’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and our plans for recovery take all segments of our population into equal account. The ADPH deserves applause for its efforts to account for racial inequities by partnering with historically Black colleges and universities and other Black-led institutions and networks in its COVID-19 vaccination planning.

Public health funding cuts haunt Alabama

Despite this collaborative approach, though, the state’s vaccination rollout got off to a troubled start. Inadequate vaccine supplies only compounded the challenge of conducting a massive public health campaign with a system undermined by chronic budget cuts. In 2019, Alabama’s state-administered county health departments operated at 65% of the professional staffing they had in 2010.[31]

The ADPH’s phased vaccine distribution plan places front-line health care workers, first responders and support personnel (e.g., hospital janitorial and medical transportation services) at the “head of the line” in Phase 1a for receiving the vaccine, along with residents and staff of nursing facilities.[32] These initial target populations are easy to identify, but some of the targets for Phases 1b and 1c – people with age- and health-related risk factors – will be more challenging to reach.

Community outreach and referral will play a critical role in successful implementation of these phases. Phase 1b also targets front-line essential workers, who are comparatively easy to identify and reach. But both this phase and the later Phases 1c and 2 include industries and general population groups that will require diversified and sustained communications and engagement.

Medicaid expansion would help ensure Alabama is prepared for the next pandemic

The COVID-19 vaccine will pose numerous logistical and economic challenges. Getting ahead of those challenges will be a key part of strengthening Alabama’s workforce as our state recovers. Let’s bring more than 340,000 Alabamians into a health care system that can provide them with accurate information, encourage them to get vaccinated and pay the cost when they do. And let’s make sure the pandemic and its associated recession don’t break our hospitals and our communities.

That’s the kind of heavy lifting Medicaid expansion was made for. Medicaid expansion is a tool for removing barriers, improving health outcomes and saving lives. Now, of all times, why aren’t we using it?

The State of Working Alabama 2021

Footnotes

[1] Alabama Department of Public Health, Alabama’s COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard, https://alpublichealth.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/6d2771faa9da4a2786a509d82c8cf0f7.

[2] Ibid.

[3] John Elflein, “Death rates from coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States,” Statista (accessed Feb. 16, 2021), https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109011/coronavirus-covid19-death-rates-us-by-state.

[4] Bama Tracker, Alabama COVID-19 Deaths, https://bamatracker.com/chart/deaths (reflecting cumulative + probable COVID-19 deaths).

[5] Congressional Research Service, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics (updated July 29, 2020), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf; Statista, “U.S. military fatalities in Iraq and Afghanistan, by state” (accessed Feb. 16, 2021), https://www.statista.com/statistics/303472/us-military-fatalities-in-iraq-and-afghanistan.

[6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups” (updated July 24, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html.

[7] Alabama Department of Public Health, Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19 Case Characteristics (April 7, 2020), https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/covid19/assets/cov-al-cases-040820.pdf.

[8] Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown & Shawn Fremstad, “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries,” Center for Economic and Policy Research (April 7, 2020), https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Employer-Sponsored Coverage Rates for the Nonelderly by Race/Ethnicity” (2019), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/nonelderly-employer-coverage-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[11] Ibid.

[12] David J. Becker, “Medicaid Expansion in Alabama: Revisiting the Economic Case for Expansion,” University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Department of Health Care Organization and Policy (Jan. 31, 2019), https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/72a465_8f37c24eeccf4e15bc6b2b97c00c3922.pdf.

[13] Alabama Arise, Medicaid Matters: Charting the Course to a Healthier Alabama, “Section 1 – How does Medicaid work in Alabama?” (June 17, 2020), https://www.alarise.org/resources/medicaid-matters-section-1-how-does-medicaid-work-in-alabama.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Alabama Arise, Medicaid Matters: Charting the Course to a Healthier Alabama, “Section 3 – Who’s still left out of health coverage in Alabama?” (June 17, 2020), https://www.alarise.org/resources/medicaid-matters-section-3-whos-still-left-out-of-health-coverage.

[16] Alabama Arise, Medicaid Matters: Charting the Course to a Healthier Alabama, “Section 4 – How can we make Alabama healthier?” (June 17, 2020), https://www.alarise.org/resources/medicaid-matters-section-4-how-can-we-make-alabama-healthier.

[17] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, April 23 – July 21, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase1.

[18] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Phase 2, Aug. 19 – Oct. 26, 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html#phase2.

[19] Alabama Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html.

[20] Arise analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, supra note 17.

[21] Arise analysis, supra note 18.

[22] Becker, supra note 12.

[23] Carol Gundlach, “How the state grocery tax hurts struggling Alabamians,” Alabama Arise (Feb. 22, 2019), https://www.alarise.org/resources/how-the-state-grocery-tax-hurts-struggling-alabamians.

[24] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map” (updated Feb. 12, 2021), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map.

[25] Tuskegee University, “About the USPHS Syphilis Study,” https://www.tuskegee.edu/about-us/centers-of-excellence/bioethics-center/about-the-usphs-syphilis-study.

[26] Reuben C. Warren, Lachlan Forrow, David Augustin Hodge, Sr. & Robert D. Truog, “Trustworthiness before Trust – Covid-19 Vaccine Trials and the Black Community, New England Journal of Medicine (Nov. 26, 2020), https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2030033.

[27] Sandra Crouse Quinn, “African American adults and seasonal influenza vaccination: Changing our approach can move the needle,” National Center for Biotechnology Information (Nov. 17, 2017), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5861789.

[28] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Influenza (Flu) General Population Vaccination Coverage” (Oct. 1, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1920estimates.htm.

[29] Jenny O’Neill, Fiona Newall, Giuliana Antolovich, Sally Lima & Margie Danchin, “Vaccination in people with disabilities: a review,” National Center for Biotechnology Information (July 24, 2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7012164.

[30] Amyn A. Malik, SarahAnn M. McFadden, Jad Elharake & Saad B. Omer, “Determinants of Covid-19 vaccine acceptance in the US,” The Lancet (Aug. 12, 2020), https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(20)30239-X/fulltext.

[31] Arian Campo-Flores, “Why Alabama Has the Worst Covid-19 Vaccination Rates,” Wall Street Journal (Feb. 11, 2021), https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-alabama-has-the-worst-covid-19-vaccination-rates-11613048418.

[32] Alabama Department of Public Health, Alabama COVID-19 Vaccination Allocation Plan (updated Jan. 29, 2021), https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/covid19vaccine/assets/adph-covid19-vaccination-allocation-plan.pdf.

Jane Adams, campaign director of Alabama Arise and director of

Jane Adams, campaign director of Alabama Arise and director of