When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Alabama in March 2020, it didn’t just cause massive human suffering and economic disruption. It also revealed suffering and disruption that have long existed and that policymakers have long neglected – or even perpetuated.

COVID-19 has laid bare deep racial and gender inequities in Alabama’s economy and social system that have left our state unprepared to meet the needs of its people in this disaster. As the workers predominantly on the front lines, women and people of color bore the brunt of the economic meltdown. They also simultaneously have suffered greater exposure to the virus that caused it.

Alabama has a weak safety net for struggling families and an approach to economic growth that all too often leaves workers underprotected and underpaid. This ongoing policy legacy has exacerbated the damage that the virus has wreaked on the state’s working people.

In The State of Working Alabama 2021, Alabama Arise explores COVID-19’s significant and negative impacts on the state’s workforce. We also look ahead to outline a state and federal policy agenda for repairing the damage – not by repeating the policy mistakes of the past, but by charting a new path toward a more equitable economy marked by broadly shared prosperity.

The lessons of COVID-19

This report makes the case that economic recovery from the COVID-19 recession requires more than restoring the former status quo. All Alabamians are eager to feel connected, productive and at ease again. But for many individuals and families across the state, disruptions and barriers to a decent, sufficient – “normal” – quality of life are nothing new.

A smart plan for restoring and expanding Alabama’s economy will take long-standing inequities explicitly into account to elevate the common good. That plan will require accommodations, supports, policies of inclusion and other interventions to create new opportunities for participation and empowerment. The result will be a post-pandemic Alabama that’s more vibrant, resourceful and equitable than the state we had before.

The spike from record low unemployment to record high in a few weeks in spring 2020 left Alabama families reeling. Many found themselves in desperate situations they never envisioned. Many others, however, have long experienced marginalization and exclusion from the workforce, or have worked for generations at low wages without benefits.

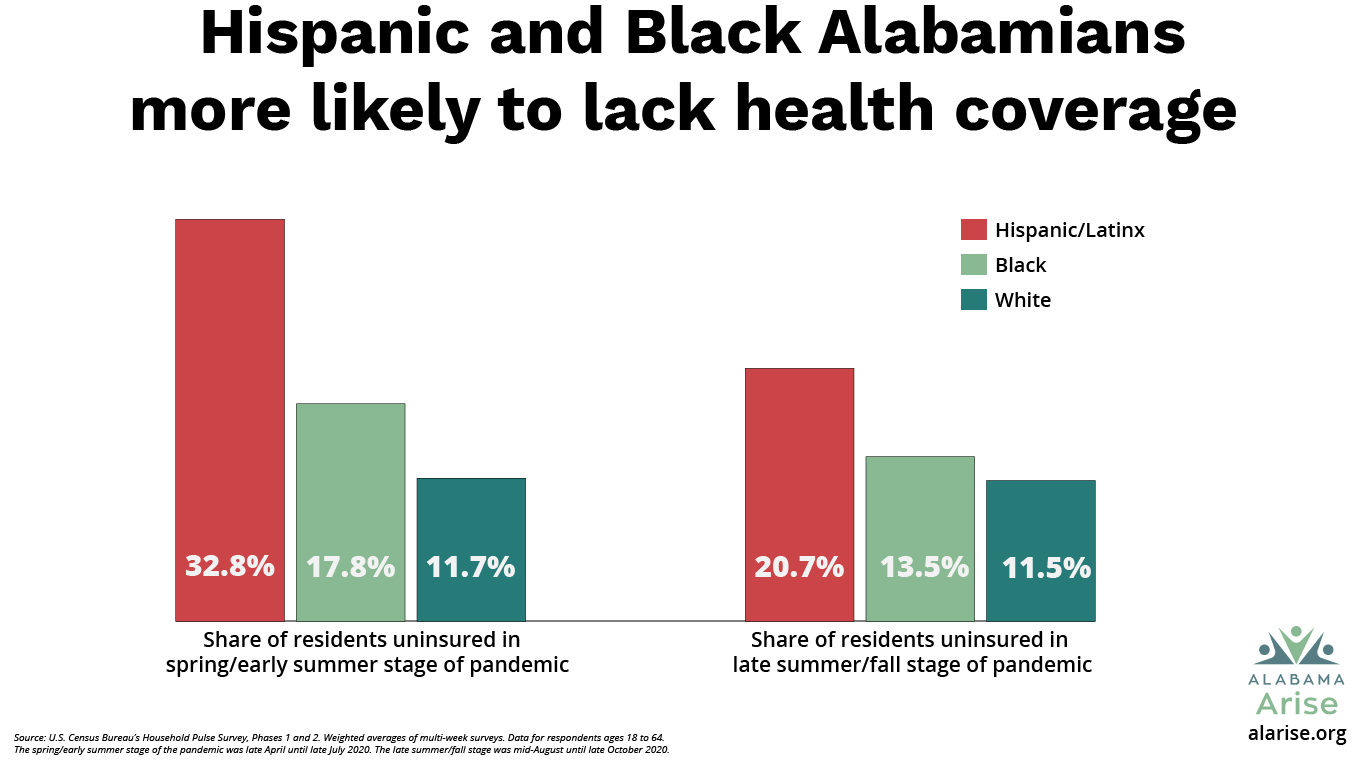

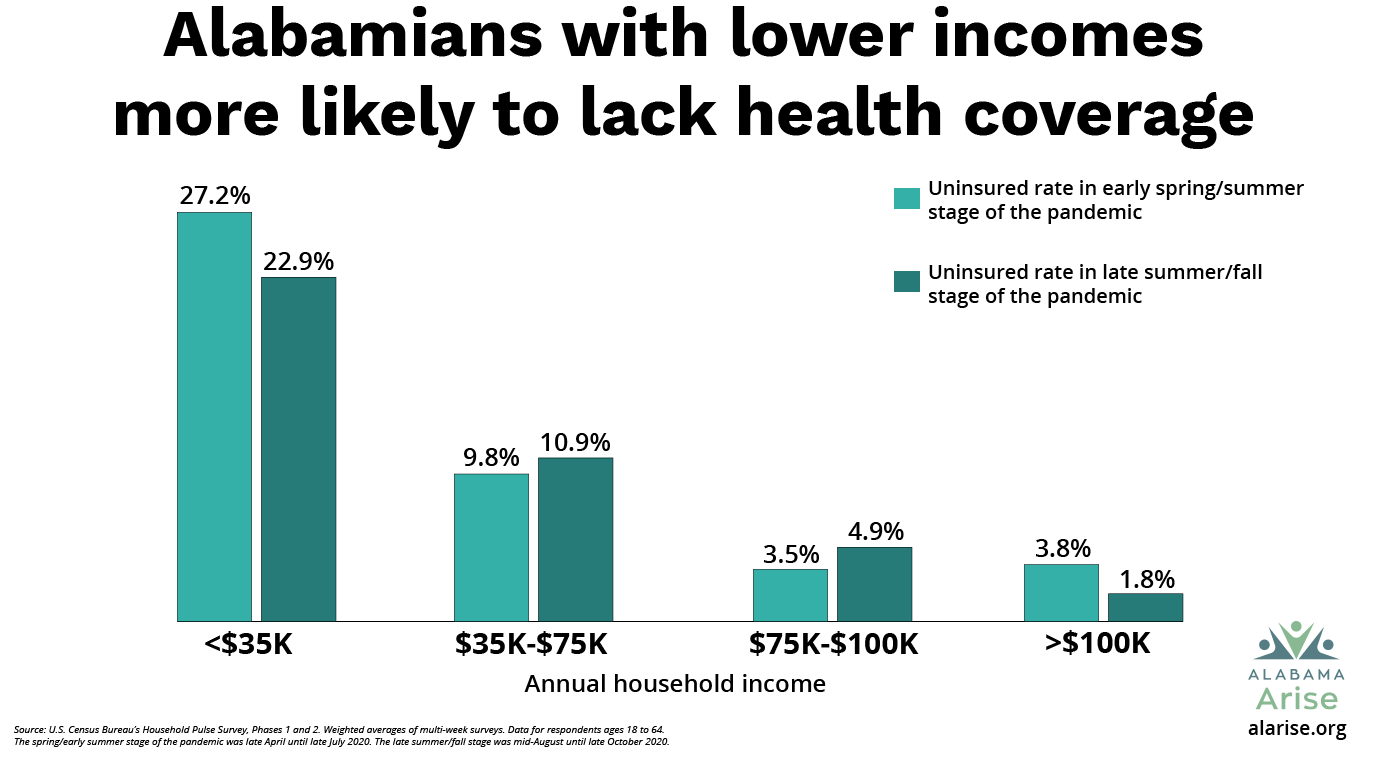

Before COVID-19, Black and Hispanic/Latinx Alabamians had significantly higher rates of poverty than white Alabamians.[1] Communities of color also experienced higher rates of medical debt in collections and defaulted student loan debt.[2] Accumulated debt from COVID-19 likely will increase this already alarming disparity. A smart recovery plan should protect workers against unreasonable debt, eviction, predatory lending and other financial burdens that will slow their ability to return to or gain economic independence.

While the COVID-19 recession has caused unprecedented layoffs, it also has highlighted the critical role of service workers in keeping our communities going. Our state leaders hail these front-line and essential workers as heroes – but often in name only, denying them the respect of decent wages and strong protections.

Shortcomings on paid leave, wages, health coverage

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act of March 2020 required many businesses to offer sick leave with full or partial pay. But this benefit expired Dec. 31, and broad exemptions left thousands of Alabama workers unprotected.

Like our Deep South neighbors, Alabama has resisted implementing mandatory paid sick leave or family medical leave for private-sector workers. Lack of paid sick leave gives underpaid working people in particular a stark choice: Continue to work while sick, or stay home and lose pay – or even lose their jobs.

Efforts to strengthen the minimum wage have begun to gain traction at last in the Deep South. Florida voters in November 2020 approved a gradual minimum wage increase,[3] the first such step in a state neighboring Alabama.

Prior to COVID-19, Alabama’s refusal to extend health coverage to adults with low incomes had already left hundreds of thousands of Alabamians in the coverage gap. Most of them are working people. They also include family caregivers, students, people awaiting disability determinations and others who have no affordable coverage option.[4]

The COVID-19 recession has only widened this coverage gap and the suffering associated with it. People without health insurance often struggle to work while dealing with health problems that sap their productivity, add stress to their households and worsen without timely care.

The changing nature of workplaces

For another range of workers and employers, the recession has transformed assumptions about how workplaces operate and how workers function. It also has raised questions about how work and family life interact and highlighted what employers are capable of doing to accommodate workers’ needs. Many changes are adaptations that people with disabilities, child care responsibilities, inadequate transportation and other challenges have sought for decades.

The surge in telecommuting is both an impressive achievement and a cautionary tale. Remote working and learning have helped many families keep their lives moving forward during the pandemic. But for households lacking high-speed broadband service, working from home doesn’t work, and children’s progress in school has stalled.[5]

Recent federal broadband grants can go a long way toward bridging Alabama’s “digital divide” if administered under strict equity guidelines and community oversight.[6] Technology access aside, many jobs are impossible to perform remotely, and this limitation falls disproportionately on low-wage workers.

Innovative public programs kept families fed

The COVID-19 pandemic and its accompanying recession have highlighted the critical role of the safety net during a crisis. Families who never before had to seek assistance suddenly found themselves unable to afford the basics of life – food, shelter, utilities, health care – and turned to public assistance for the first time.

Enrollment for food assistance under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) rose 12% between February 2020 and October 2020.[7] Federal waivers allowed the Department of Human Resources (DHR) to cut red tape and increase assistance for most SNAP participants. State and county SNAP workers worked nights and weekends to process more than 83,000 new SNAP applications.[8]

DHR and the state Department of Education also partnered to create – in just weeks – an entirely new program, called Pandemic EBT (P-EBT), that replaced school meals lost when schools closed.[9] By the end of the 2019-20 school year, P-EBT had distributed at least $132 million in food assistance to more than 420,000 Alabama children.[10]

Meanwhile, workers in school districts and emergency food closets across the state risked their own health to distribute federally funded school meals and food boxes to hungry families waiting in lines that ran for blocks. Federal Emergency Solutions Grants will help community-based agencies prevent an eviction epidemic if a federal moratorium ends in 2021.[11]

Efforts to cut the safety net are cruel and shortsighted

For the past five years, the Alabama Legislature has attempted to cut and restrict critical safety net programs. Fortunately, those efforts largely have failed because of hard work by advocates and directly affected Alabamians. The one safety net restriction that lawmakers approved – reducing the time workers could receive unemployment insurance (UI) benefits – was effectively reversed briefly when the state Department of Labor implemented federal extended benefits (EB) that were available because Alabama’s reported unemployment rate had exceeded 5.9%. But this reversal of the state’s policy failure was only temporary. The EB program has stopped paying benefits as of Oct. 3, 2020.[12]

Had proponents of safety net cuts been more successful, critical programs like Medicaid, SNAP and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) might have not been available to meet Alabamians’ most basic needs today. Our leaders should remember this moment and the importance of the safety net as they prepare for future emergencies.

How we should respond now

Alabama is a torchbearer to the nation for civil and human rights achievements. We boast a world-class medical research center and regional hubs of education, business, manufacturing and finance. Our rich cultural legacy has produced artists of world renown.

But these proud assets stand against a backdrop of low wages, lingering rural and urban poverty, and racial injustice rooted in slavery and violent oppression. These structural failures have created unequal access to basic necessities, education and economic opportunity; wide health disparities; and other violations of the common good.

The COVID-19 crisis has created new challenges for our state and worsened persistent ones. If there is a bright spot to be found, it is in the light the pandemic has shined on these old problems and on new ways we can and must address them. We call on our leaders to envision a new Alabama beyond the pandemic horizon, where all residents can share in the best the state has to offer.

In focus

The Household Pulse Survey: An important new source of data on the pandemic’s impact on Alabamians

Shortly after the pandemic began, the U.S. Census Bureau launched the Household Pulse Survey to get a sense of the rapid changes occurring in people’s lives and livelihoods.[13] A sample of residents from every state answered questions – weekly for several months, then later every two weeks – about how the pandemic was affecting their household finances, health, education and other social and economic activities.

The survey asked people questions like:

- Have you or anyone in your household experienced a loss of income since March 13?

- In the last seven days, how difficult has it been for your household to pay for usual expenses?

- How confident are you that your household will be able to afford the food you need for the next four weeks?

- How confident are you that your household will be able to pay your next rent or mortgage payment on time?

We now have more than 20 installments of Alabama responses to this survey, and they are both frightening and telling. These responses inform much of this report. They provide snapshots of the impact of the pandemic and resulting recession on Alabamians’ economic and employment status. They provide crucial information about Alabamians’ ability to pay bills, access health care and participate in education. And they show us how people are making ends meet – or not – during the crisis.

Snapshots of pandemic life in Alabama

The Household Pulse Survey has rolled out in three phases, reflecting stages of the pandemic. The spring/early summer stage ran from late April until late July. The late summer/fall stage ran from mid-August until late October. And the winter stage runs from Oct. 28 until March 2021.

Because the questions have been tweaked and the frequency of the survey has changed between the phases, we can’t compare results in one phase to that in others, so we have to treat each stage as its own snapshot during each season of the pandemic. It’s important to know, too, that not everyone who answered the survey answered every question. Some survey questions have a high “non-response rate,” which could skew our understanding of the results. Household Pulse data included in this report does not include non-responses. While these caveats limit the conclusions we can draw from the data, the survey nonetheless offers valuable real-time reporting on the pandemic’s profound and far-reaching impact on our state.

Click here for more information on the survey.[14]

The State of Working Alabama 2021

Footnotes

[1] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity,” State Health Facts 2019, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[2] Urban Institute, “Debt in America: An Interactive Map” (Dec. 17, 2019), https://apps.urban.org/features/debt-interactive-map/?type=overall&variable=pct_debt_collections&state=1.

[3] Andrea Hsu, “Florida Just Passed a $15 Minimum Wage. Is the Time Right for a Big Nationwide Hike?,” NPR (Nov. 18, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/11/18/934476124/florida-just-passed-a-15-minimum-wage-is-the-time-right-for-a-big-nationwide-hik.

[4] Alabama Arise, Medicaid Matters: Charting the Course to a Healthier Alabama, “Section 3 – Who’s still left out of health coverage in Alabama?” (June 17, 2020), https://www.alarise.org/resources/medicaid-matters-section-3-whos-still-left-out-of-health-coverage.

[5] A+ Education Partnership, “No Child Left Offline: Tackling the Digital Divide in Alabama” (Aug. 17, 2020), https://aplusala.org/blog/2020/08/17/no-child-left-offline-tackling-the-digital-divide-in-alabama.

[6] U.S. Department of Agriculture, “USDA Invests $62.3 Million in Rural Broadband Infrastructure for Alabama Families” (Dec. 5, 2019), https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2019/12/05/usda-invests-623-million-rural-broadband-infrastructure-alabama.

[7] Alabama Department of Human Resources (DHR), Detailed Monthly Statistical Reporting for DHR Services, Table 19: Food Assistance Program (February 2020), https://dhr.alabama.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/STAT0220.pdf; ibid. (October 2020), https://dhr.alabama.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/STAT1020.pdf.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Celida Soto Garcia, “P-EBT, rapid school actions keep Alabama children fed,” Alabama Arise (Sept. 23, 2020), https://www.alarise.org/blog-posts/p-ebt-rapid-school-actions-keep-alabama-children-fed.

[10] Koné Consulting, Report: Pandemic EBT Implementation Documentation Project 13 (September 2020), https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/P-EBT-Documentation-Report.pdf.

[11] Benefits.gov, “Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG),” https://www.benefits.gov/benefit/5890.

[12] Alabama Department of Labor, “ADOL Announces Extended Benefits Program to Expire: Benefits to Continue Through October 3” (Sept. 14, 2020), https://labor.alabama.gov/news_feed/News_Page.aspx?id=274.

[13] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey Data Tables, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html.

[14] U.S. Census Bureau, “Household Pulse Survey: Measuring Social and Economic Impacts during the Coronavirus Pandemic,” https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey.html.

Jane Adams, campaign director of Alabama Arise and director of

Jane Adams, campaign director of Alabama Arise and director of