COVID-19 revealed a stark reality about Alabama’s economy from the beginning: Our state has stacked the deck against underpaid working people. A high poverty rate, low educational attainment and poor health outcomes – with racial, ethnic and geographical disparities in all of these measures – are the results of low wages, low taxes and low funding for health care, education and other basic services.[1] These are all low-road policies that will not strengthen our economy or improve Alabamians’ quality of life.

These patterns reflect centuries of racial and economic oppression. They are grounded in slavery and prolonged by our explicitly white supremacist 1901 state constitution. Alabama voters acknowledged this shameful legacy and took a step toward dismantling it in November 2020, when they approved an amendment to remove racist provisions from the constitution.[2] The amendment passed by a 2-to-1 margin.[3]

Public school segregation, poll taxes and prohibition of “mixed-race” marriage already had been successfully challenged through federal lawsuits and legislation. But striking them from the cornerstone of state law lifts a symbolic barrier to equality. Strong statewide support for the measure suggests the time is right to tackle more substantial and intractable barriers like the ones described in this report.

Despite barriers, Alabama’s labor movement persists

COVID-19 has highlighted the state’s long-standing low regard for protecting Alabama’s working people. Worker protections have a checkered history in Alabama, not surprisingly for a state powered by an enslaved workforce in its first five decades. Systematic labor exploitation continued into the 20th century, both in agriculture under the sharecropper system and in industry under convict leasing.

But the industrial boom around Birmingham in the late 1800s, and later in Mobile, ushered in an organized labor movement. The movement has waxed and waned in response to wartime and peacetime economies, race relations, industrial trends and globalization, but it has never completely gone away. At 8% of the workforce, Alabama’s union membership rate remains the highest in the South.[4]

A stacked policy deck against working Alabamians

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Alabama has adopted a “red carpet” approach to industrial development, granting generous tax abatements and other incentives while failing to modernize wage levels[5] and worker benefits.[6] Stacking the deck against workers created a “preexisting condition” that intensified the impact of COVID-19, hindering the state’s ability to respond to massive economic disruption and to mitigate its effects on working families.

In pursuing this low-road approach, Alabama has prioritized low wages and low taxes over investing in the state’s people. The result is an economy that disadvantages wage workers and people of color. A major force in this inequity is our “right-to-work” laws, which date to the 1950s. These and related laws severely weaken worker rights in Alabama and allow proliferation of low-wage jobs, sometimes with hazardous conditions.

”Right-to-work” laws make it harder for unions to organize, limit unions’ bargaining power and decrease their budgets.[7] In turn, these outcomes often result in suppressed wages and diminished political power for working people. Where unions do exist in Alabama, “right-to-work” laws undermine their effectiveness, entitling non-union workers to union benefits without paying dues. Manufacturing jobs, typically known for their strong union presence, account for about 13% of employment – more than 200,000 jobs – in Alabama.[8]

Preemption limits local power to solve local problems

Another state policy that has left working Alabamians unprepared to deal with the economic burden of COVID-19 is preemption. Rooted in post-Reconstruction attempts to suppress and disenfranchise Black people in the Deep South, preemption is the use of state law to nullify municipal authority.[9] It remains a popular tool for white, conservative legislators seeking to strike down progressive policies from large, majority Black urban areas.

Alabama used preemption twice in the last decade to reverse popular municipal ordinances that strengthened worker rights. In 2016, the Legislature struck down a Birmingham ordinance to raise the city’s minimum wage to $10.10. This move effectively denied wage increases for 65,000 workers – who were disproportionately women and disproportionately Black.[10]

In February 2020, after the Montgomery City Council implemented a 1% occupational tax to support public services and hire more public employees,[11] the Legislature immediately nullified it.[12] The preemption measure requires cities to obtain legislative approval before levying taxes above the levels in place on Feb. 1, 2020. In both cases, Alabama’s majority white Legislature blocked policies that would have strengthened worker protections in predominantly Black cities (69.2% in Birmingham, and 60.8% in Montgomery).[13]

COVID-19 reveals need for pro-workforce policies

Ultimately, Alabama’s failure to strengthen worker protections and raise the wage floor amplified the pandemic’s impact. Thousands of underpaid working people lost their jobs, with little or no savings to fall back on afterward. Those who continued to work often did so in dangerous conditions without paid sick leave, health insurance or a living wage. As we chart Alabama’s course of economic recovery, balancing “pro-business” policies with pro-workforce ones will be key to long-term success.

A case in point is the issue of corporate immunity from COVID-19 liability claims.[14] Alabama legislative leaders identified this as a top priority for 2021 and rushed to enact it early in the regular session.[15] Many businesses, health care providers and other employers favor protection from what they see as the threat of lawsuits that could slow the reopening process. But liability poses low risk to businesses because the virus’s relatively long incubation period makes it difficult to prove exposure happened at a particular time and place.

By contrast, broad corporate immunity will increase the COVID-19 risk for workers and consumers.[16] Immunity reduces the incentive for employers and establishments to protect people from exposure. Without legal recourse for the health and financial consequences of COVID-19 illness, workers in unsafe workplaces may find themselves in a difficult bind: Risk exposure by clocking in – often without health insurance and sick leave – or risk getting fired by staying home. A balanced approach to corporate immunity would include expanding health coverage and workers’ compensation for low-wage workers.

One pandemic, many different experiences

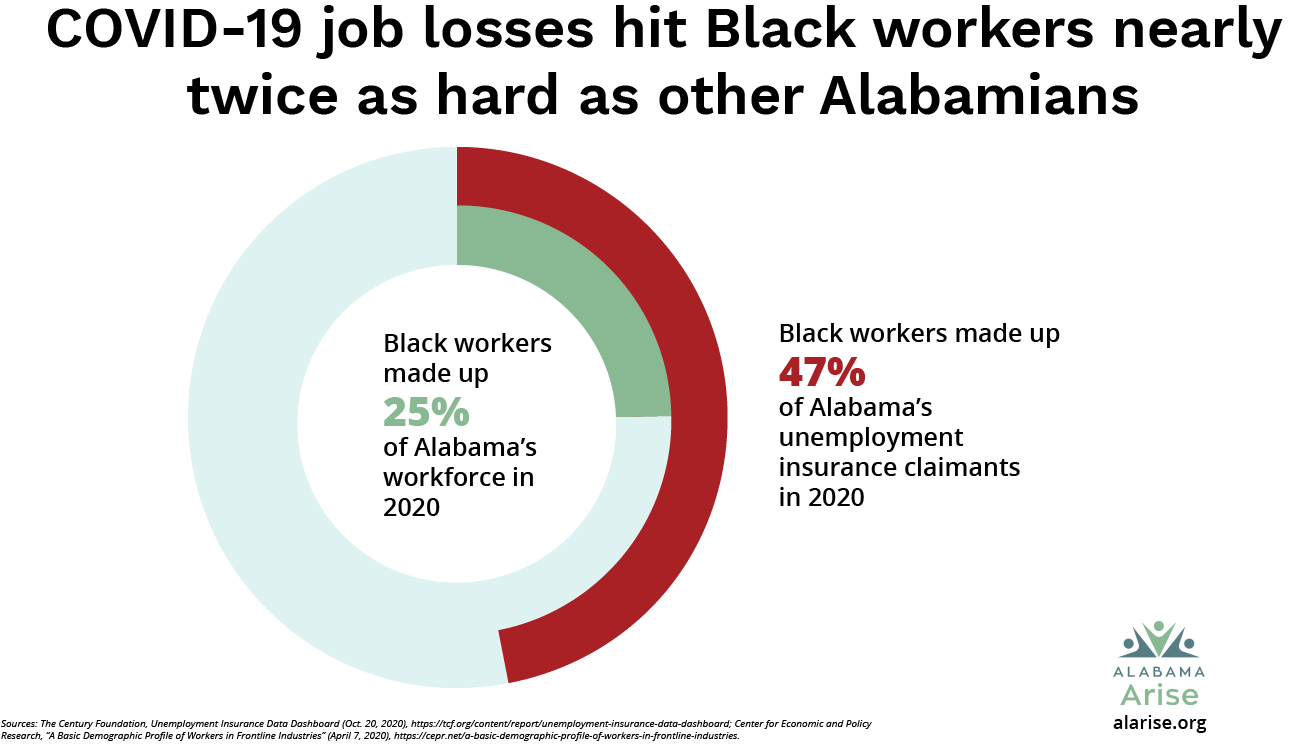

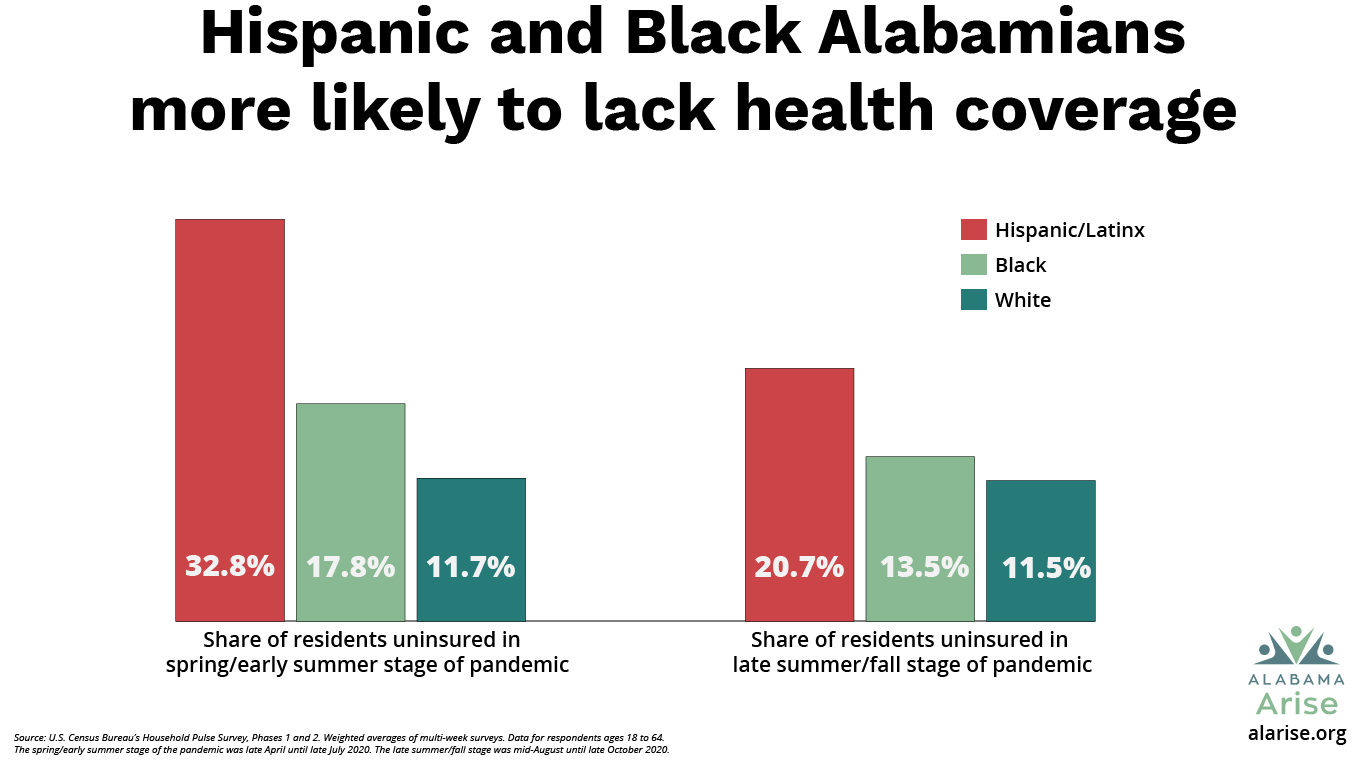

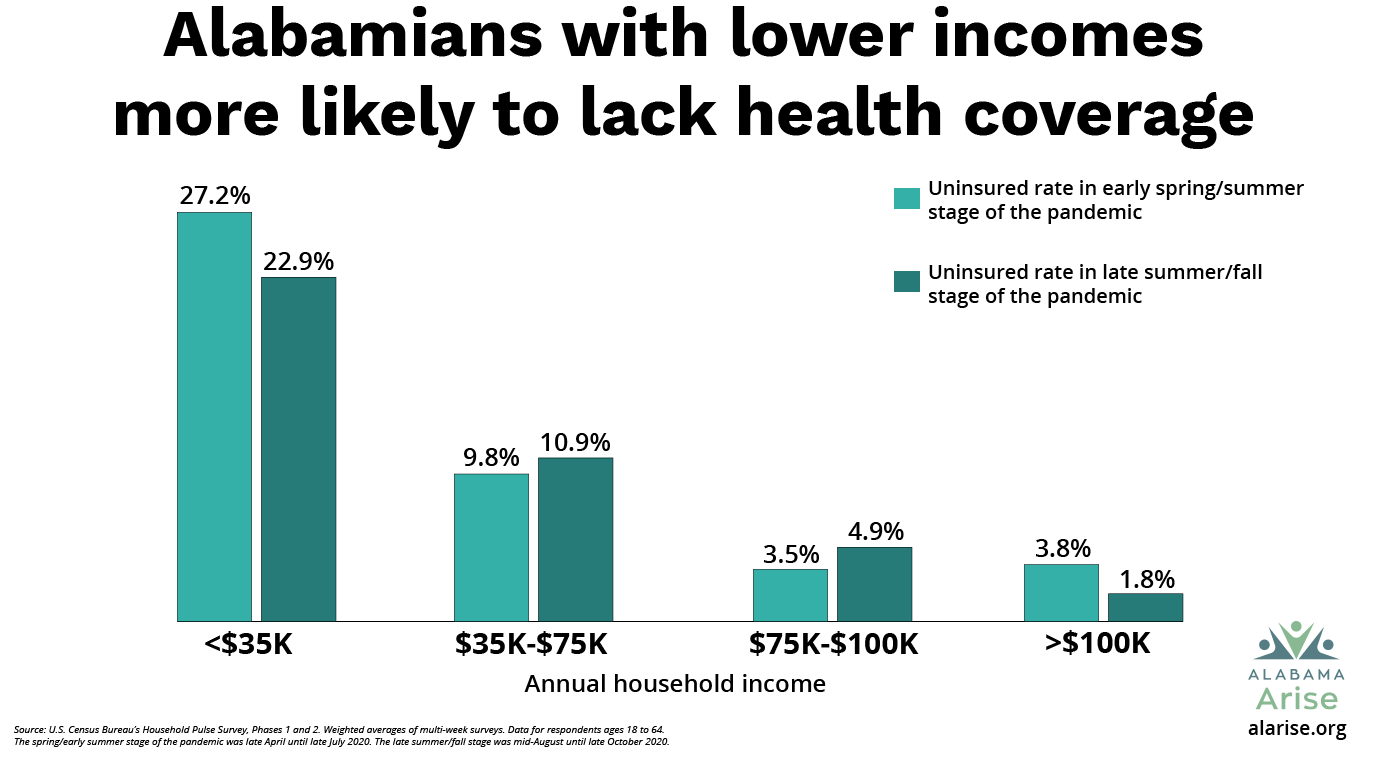

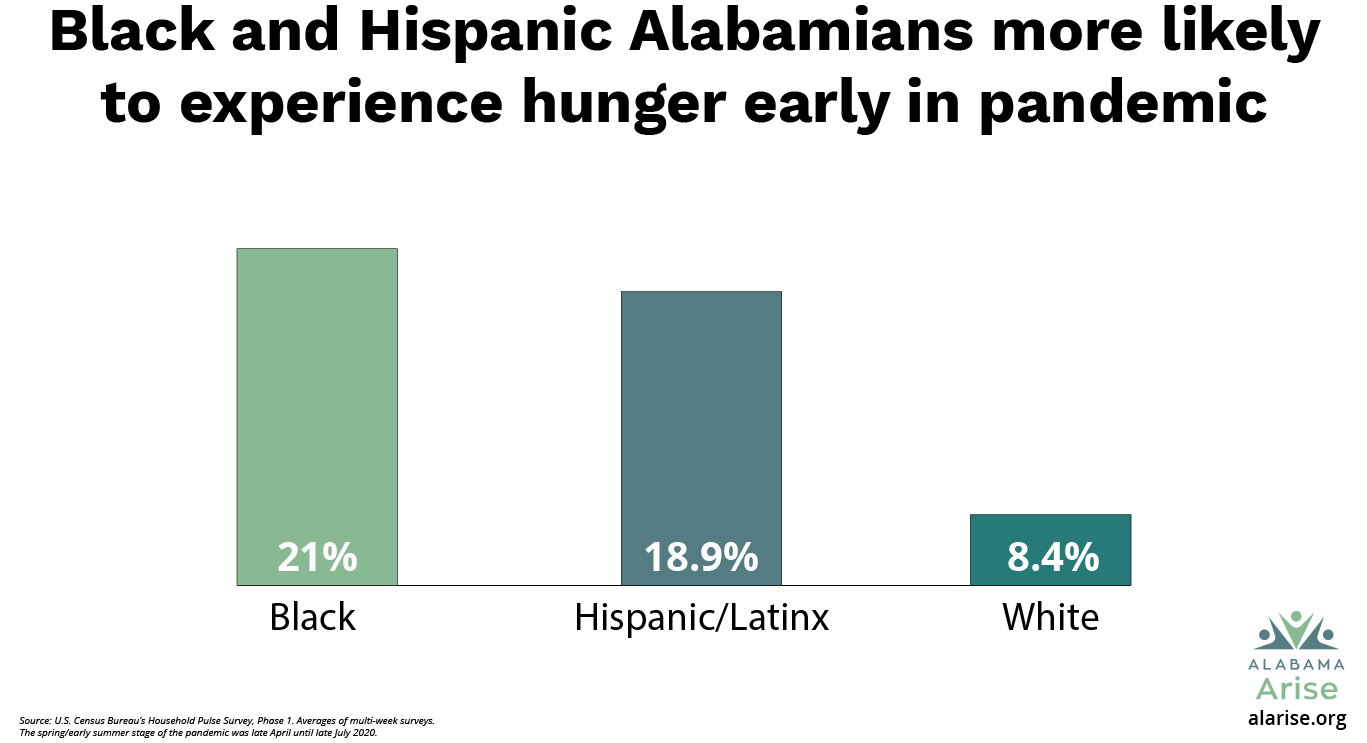

In its ability to strike anyone at any time under the right circumstances, COVID-19 is an equal opportunity threat. But the experience of COVID-19 and its impact on lives and livelihoods varies widely across racial, ethnic and economic groups. Other sections of The State of Working Alabama 2021 will examine these disparate effects on Alabamians’ labor market, health coverage, food security and other workforce conditions.

The State of Working Alabama 2021

Footnotes

[1] County Health Rankings, “2020 Alabama Report,” https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/reports/state-reports/2020-alabama-report.

[2] Jim Carnes, “Why Alabama Arise supports Amendment 4,” Alabama Arise (Oct. 16, 2020), https://www.alarise.org/blog-posts/why-alabama-arise-supports-amendment-4.

[3] Brian Lyman, “Alabama votes to allow purge of racist constitutional language,” USA Today (Nov. 6, 2020), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/11/06/alabama-votes-allow-purge-racist-constitutional-language/6185508002.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by state, 2018-19,” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t05.htm.

[5] Alabama Asset Building Coalition, Advancing Employment Equity in Alabama (April 2018), https://nationalequityatlas.org/sites/default/files/Employment_Equity-Alabama_04_03_18.pdf.

[6] Diana Boesch, Rachel Kershaw & Osub Ahmed, “Fast Facts: Economic Security for Women and Families in Alabama,” Center for American Progress (Aug. 8, 2019), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/08/08/473358/fast-facts-economic-security-women-families-alabama.

[7] See, e.g., Alex Camardelle, “Worker Power Key to a Better Balance in Georgia,” Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (Sept. 3, 2020), https://gbpi.org/worker-power-key-to-a-better-balance-in-georgia.

[8] National Association of Manufacturers, “2019 Alabama Manufacturing Facts,” https://www.nam.org/state-manufacturing-data/2019-alabama-manufacturing-facts.

[9] National League of Cities Center for City Solutions, “City Rights in an Era of Preemption: A State-by-State Analysis,” 2018 Update, https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/NLC-SML-Preemption-Report-2017-pages.pdf.

[10] Hunter Blair, David Cooper, Julia Wolfe & Jaimie Worker, “Preempting Progress,” Economic Policy Institute (Sept. 30, 2020), https://www.epi.org/publication/preemption-in-the-south.

[11] Sara MacNeil, “City passes 1% tax on people who work in Montgomery,” Montgomery Advertiser (Feb. 19, 2020), https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/2020/02/19/city-passes-1-percent-tax-people-who-work-montgomery/4781312002.

[12] Mike Cason, “Alabama lawmakers pass restriction on city occupational taxes,” AL.com (Feb. 28, 2020), https://www.al.com/news/2020/02/alabama-lawmakers-pass-restriction-on-city-occupational-taxes.html.

[13] Blair, et al., supra note 10.

[14] Paul Dowdell, “Immunity from Liability in the Age of COVID-19: A New Reality for Trial Lawyers?,” American Bar Association (Aug. 31, 2020), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/trial-practice/articles/2020/immunity-from-liability-covid-19-trial-lawyers.

[15] Abby Driggers, “Gov. Ivey signs COVID-19 liability bill into law,” Opelika-Auburn News (Feb. 12, 2021), https://oanow.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/gov-ivey-signs-covid-19-liability-bill-into-law/article_3084205e-6d3b-11eb-94c6-dbaf546e98c8.html.

[16] Alabama Arise, “Alabama Arise testimony in opposition to corporate COVID-19 immunity bill” (Feb. 3, 2021), https://www.alarise.org/resources/alabama-arise-testimony-in-opposition-to-corporate-covid-19-immunity-bill.