A state Senate committee approved a bill Wednesday to cut new holes in Alabama’s safety net.

Issue: Budgets

Arise legislative recap: April 19, 2019

“The grocery tax is a tax on a basic necessity of life. It’s a tax on survival. And it’s time for Alabama to bring this tax to an end.”

Arise communications director Chris Sanders discusses a recent bill by Rep. Chris England that would be a major step forward on untaxing groceries. The video also details Arise’s plan for how Alabama could end the state grocery tax and expand Medicaid without cutting a dime from the education budget.

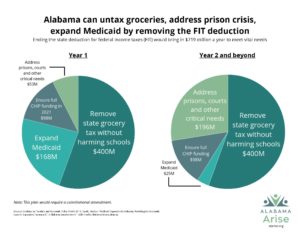

Removing the FIT deduction would allow Alabama to untax groceries, expand Medicaid

Alabama’s federal income tax (FIT) deduction provides a huge tax break for high-income individuals – but at what cost? $719 million to be exact.

The FIT deduction is one big reason Alabama’s tax system is upside down. For those who earn $30,000 a year, the deduction saves them about $27 on average. But for the top 1% of taxpayers, the FIT break is worth an average of more than $11,000. The higher the income, the more the FIT deduction is worth for those who can most afford to pay more to fund education, health care and other vital needs.

Only two other states offer a full FIT deduction like Alabama does. (Three other states offer a partial deduction.) Ending the FIT deduction would bring in an additional $719 million a year, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimates. That would be enough to allow Alabama to remove the state sales tax on groceries. For most people in our state, the net result would be a tax cut.

This proposal would make it easier for everyday Alabamians to make ends meet, but its benefits wouldn’t end there. Alabama also could use the new revenue to expand Medicaid, ensure full funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 2021 and make critical investments in education and other areas. CHIP supports health coverage for more than 170,000 children through Medicaid and ALL Kids.

Alabama’s constitution dedicates income tax revenue to education, and the FIT deduction is written into the document as well. So this plan would require the Legislature and the public to approve a constitutional amendment. But ending the FIT deduction would be a good way for Alabama to begin prioritizing public investments that benefit everyone over tax breaks that primarily benefit a select few.

The real story of the House’s 2020 General Fund budget is what isn’t in it

Now that the gas tax is a reality, the Alabama Legislature appears to be in a hurry to finish up essential business – and maybe even adjourn a little early. The House on Tuesday passed a General Fund (GF) budget that differed little from Gov. Kay Ivey’s recommendations.

With Alabama finally out of the worst of the recession and revenues beginning to flow again, many legislators seem to be feeling a bit like Santa Claus. But the real story is what’s not under the GF’s tree.

The House’s GF budget, which awaits Senate action, would squeeze out increases for nearly every state agency, most of which have been living through tight times for the last decade. The state’s badly cash-strapped court system would receive nearly $40 million more, hopefully reducing its dependence on fines and fees. The Department of Corrections, facing court challenges over treatment for inmates with cognitive disabilities, would get an additional $41 million. That money would allow the department to hire an additional 500 prison guards.

Helping agencies would get increases, too. Mental health would receive an additional $9 million, as would the Department of Human Resources (DHR). The small but vital Department of Senior Services would get an additional $1 million.

Even state employees, who haven’t seen a pay increase in years, would get a 2% cost of living increase. And retired state employees would receive a one-time bonus based on the number of years served.

The head-scratcher budget request came from Medicaid. For years now, Medicaid’s funding needs have challenged previous bare-bones GF budgets. Now, during a good revenue year, Medicaid Commissioner Stephanie Azar actually requested $52 million less. Azar said the agency can carry over a considerable sum from this year to maintain current services in 2020.

The investments our state isn’t making

The 2020 GF budget does indeed look pretty good at first glance. But the House plan is conspicuous for what was not included.

Perhaps most notably, the budget doesn’t fund Medicaid expansion to cover more than 300,000 Alabama adults with low incomes. The net state cost would be $164 million in the first year and about $25 million a year thereafter. The $52 million reduction in Medicaid’s budget would have made a nice down payment on expansion.

While the Department of Corrections can hire another 500 prison guards, the real need is closer to 2,000 new guards, according to a federal court order. And the budget does not include money for the new prison construction that Ivey has urged.

Lawmakers transferred ALL Kids to the education budget for 2020 to help balance the GF budget. But House GF budget committee chairman Rep. Steve Clouse, R-Ozark, said ALL Kids will move back to the GF in 2021. That move would add to the strain that the underfunded GF budget regularly faces. To draw down available federal matching money, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) will need $98 million more from the state in 2021 than it receives today. CHIP provides health coverage for more than 173,000 Alabama children through both ALL Kids and Medicaid.

A funding solution to help everyday Alabamians

Alabama is, quite simply, in need of new revenue. And Alabama Arise has a plan to raise that revenue while giving most residents an overall tax cut.

Alabama is one of only three states that allow taxpayers to deduct all of their federal income tax (FIT) payments from their state income taxes. This tax loophole makes little (if any) difference for families with low and moderate incomes. But it saves millionaires a whopping average of $11,327 a year in state income taxes. If Alabama ended its FIT deduction, the state would bring in an additional $719 million a year.

That new money would allow Alabama to expand Medicaid and end the state grocery tax (two long-time Arise priorities). It also would ensure full CHIP funding in 2021 and leave additional money to meet other critical needs. (Because the state constitution earmarks income tax revenue for education, some of those moves would require an amendment.)

The proposed 2020 GF budget is only flush when compared with years when the state was truly in dire straits. It’s time for our lawmakers to find the political courage to address Alabama’s needs and raise the revenue required to meet them. Ending the state’s FIT deduction would be a good first step.

Arise legislative recap: April 12, 2019

“While the General Fund budget looks really good for what it is, what it is is not enough.” Arise policy analyst Carol Gundlach breaks down what’s missing from the General Fund budget that the Alabama House passed April 9.

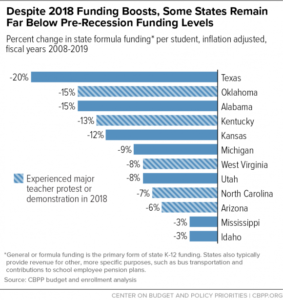

Alabama’s K-12 funding still far lower than a decade ago, despite recent gains

Alabama increased state education funding in 2018, but the legacy of years of extreme cuts remains, according to a new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a nonpartisan research organization based in Washington, D.C.

Alabama increased its K-12 formula funding by 1 percent per student last year. But that funding is still far below pre-recession levels: 15 percent less per student after adjusting for inflation.

“It’s good that state K-12 funding is moving in the right direction again, but Alabama must do much more to get our education system back on track,” Alabama Arise executive director Robyn Hyden said. “Otherwise, we risk falling even further behind states that invest more in their schools.”

Formula funding is the main state revenue source for K-12 schools nationally. It is especially important for schools in high-poverty areas, which educate a disproportionate share of black and Hispanic children. But state cuts have forced many cities and counties to cover more of the cost of education. Between 2008 and 2016, the national average for state funding declined by $167 per student. Average local funding grew by $161 during that time.

“The effects of state funding cuts are evident in teacher pay. Some 42 states cut the average teacher’s salary relative to inflation between 2010 and 2017,” said Michael Leachman, CBPP’s senior director of state fiscal research. “That is why teacher protests have emerged in many states recently.”

Adequate school funding can strengthen state economies. But steep funding cuts make it hard for states to reduce class sizes, extend learning time and enact other reforms to help students thrive.

“Alabama should close income tax loopholes that overwhelmingly benefit wealthy people and large corporations,” Hyden said. “That would allow our state to boost investments in K-12 education and offer pre-K to all families. And it would increase economic opportunities for low-income students and communities of color, who face the greatest barriers to education.”

How to advance our vision for Alabama’s next century

What kind of future do we want for Alabama? It’s a question worth reflecting on as our state enters its third century this year. Are we all right with limiting power and prosperity to a select few? Or would we rather build a state where everyone has a voice and where people of all races, genders and incomes have a real chance to get ahead?

Alabama Arise believes in justice and opportunity for all, and our policy priorities flow from that vision. It’s why we support expanding Medicaid for Alabamians who can’t afford coverage. It’s why we want to rebalance an upside-down tax system that taxes struggling families deeper into poverty. And it’s why we urge stronger investments in education, housing, public transportation and other services that improve quality of life and promote economic opportunity.

We expect lots of infrastructure talk at the Legislature this year. The regular session starts Tuesday, but lawmakers may move quickly into a special session on the gas tax. Gov. Kay Ivey has asked legislators to increase the state’s 18-cent gas tax by 10 cents over three years. That money would fund road and bridge maintenance and other infrastructure improvements.

Many of Alabama’s deteriorating roads are overdue for repair. But the definition of “public infrastructure” goes far beyond tar and gravel. Education, health care and public transportation also help lay the foundation for shared prosperity. This session could bring chances to strengthen those investments – and to make the tax system that funds them more progressive.

Hope on grocery tax, Medicaid expansion

One key breakthrough could be on a longtime Arise priority: ending the state grocery tax. We came heartbreakingly close in 2008, when a bill to untax groceries passed the House and fell one vote short in the Senate. But Arise members never gave up the advocacy fight. Now legislators face renewed pressure to end or cut the state’s 4 percent sales tax on groceries. (Some conservative lawmakers are urging a grocery tax reduction to accompany a gas tax increase.) Alabama is one of only three states with no tax break on groceries. It’s a highly regressive tax on a basic necessity, hitting hardest on people who struggle to make ends meet.

Pressure also is building for Alabama to expand Medicaid to cover more than 340,000 adults with low incomes. Medicaid expansion would save hundreds of lives annually and create a healthier, more productive workforce. It also would help save rural hospitals, support thousands of jobs and pump hundreds of millions of dollars into the economy.

Our work for a brighter, more inclusive future won’t end there. We’ll keep pushing for stronger consumer protections against high-cost payday loans. We’ll make the case for the state to fund public transportation and remove barriers to voter registration. And we’ll continue seeking an end to injustices in Alabama’s civil asset forfeiture and death penalty systems. Visit our website and follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates on these issues throughout the year.

Budget hearings show need for Alabama to expand Medicaid, boost public investments

Alabama needs to expand Medicaid and invest more in education and other human services. Those were key takeaways from this week’s state budget hearings in Montgomery. The hearings highlighted a range of policy challenges and illustrated the connections between many of them.

We heard a lot of talk this week about the need to strengthen Alabama’s “infrastructure.” Many legislators say the state just doesn’t have enough money to make further investments in human infrastructure – the services like health care, child welfare and public safety that serve as a basic measure of what we value. But that’s incorrect.

Alabama’s lack of money for education, health care, child care and other services isn’t a natural force like the weather. It’s the result of decades of policy choices, as our Tax & Budget Handbook shows. And better choices can lead to better outcomes for Alabama.

Medicaid expansion could cut costs for corrections, DHR

Numerous agency leaders identified Alabama’s fraying rural health care system as a major concern. Rural hospital closures hurt communities and make it harder to get care. A lack of mental health care takes a toll on families, schools and workers. And both challenges increase financial strain on the corrections system.

The opioid epidemic is one problem that cuts across multiple areas: corrections, education, human resources, law enforcement, Medicaid, mental health and public health. Many parents fighting addiction lose child custody to the Department of Human Resources (DHR), which struggles to recruit foster parents for an average $16 daily allowance.

While bare-bones health agencies tackle the epidemic’s medical consequences, Alabama’s corrections system has emerged as the largest provider of mental health services, with many of them linked to substance use disorders.

That’s true even as Alabama’s prison overcrowding remains staggeringly high. The state prison system once operated at nearly double its designed capacity. Recent sentencing reforms helped cut that rate to 163 percent, and Corrections Commissioner Jeff Dunn expects it to sink to 145 percent. But further reductions are unlikely without broader changes, Dunn said.

Rural hospital closures affect prison overcrowding, too. Sen. Cam Ward, R-Alabaster, said a private prison in Perry County is vacant despite an appropriation to buy it. The county has no hospital, which would make it hard to use the prison even if the state bought it, Ward said.

Medicaid expansion would cut costs and improve lives across all these areas of concern. It would stem the tide of rural hospital closures. It would expand access to mental health and substance use treatment. And that would save many Alabamians from going to jail or losing child custody. Arise members and other advocates must keep making the case for Medicaid expansion throughout 2019.

Decades of inadequate funding cause unmet needs, staff shortages

Our state’s upside-down tax system requires most Alabamians to pay twice the share of income in state and local taxes that the richest households pay on average. It also means Alabama struggles to raise enough money to fund health care, child welfare and other important services.

Staff shortages were a running theme at this year’s budget hearings. Alabama’s corrections and mental health commissioners both emphasized problems with hiring and keeping qualified employees. DHR cited high turnover in child welfare staff, who are first on the scene when children’s safety is at risk. And the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA) needs more state troopers to ensure highway safety.

DHR Commissioner Nancy Buckner asked lawmakers for an additional $21 million for 2020. Buckner said DHR struggles to retain staff, especially in the stressful child welfare division, which has 36 percent turnover. “Anything you can see on TV, we probably have multiple cases,” Buckner said.

The new money would allow for salary increases, technology improvements, and higher payments for foster families, Buckner said. Foster parents are difficult to recruit, she said, and the opioid epidemic has left more children in foster care.

For corrections, Dunn asked for another $42 million to hire and retain 500 prison guards and improve mental health services. (Low unemployment makes it harder to retain officers, Dunn said, because they often can earn more at safer jobs.) A federal judge has ordered Alabama to address its guard shortage and inadequate health services in state prisons.

ALEA Secretary Hal Taylor requested another $8.7 million to provide raises and hire 50 new state troopers. Up to 200 troopers could retire soon, Taylor said, and ALEA must compete with other departments for officers.

K-12 schools seek to hire more teachers, expand mental health support

Alabama schools discussed their needs for 2020 as well. State school Superintendent Eric Mackey requested an additional $295 million from the Education Trust Fund. With that money, schools could hire more teachers in grades 4-6 and invest more in the Alabama Reading Initiative. They also could hire more school nurses and provide a $600 allowance per teacher for classroom supplies.

Mackey asked for an extra $270 per student to teach about 25,000 students for whom English is a second language. And he requested another $22 million for school safety improvements and school-based mental health services.

Mackey echoed other agency heads by raising concerns about future personnel shortages. A recent survey of high school seniors found only 4 percent want to become teachers, down from 12 percent in previous surveys, Mackey said.

Sen. Vivian Figures, D-Mobile, asked Mackey to address the state Department of Education’s listing of 76 schools as “failing.” Most of those schools are in low-income areas and serve mostly black students. Mackey said the Alabama Accountability Act requires him to designate the lowest performing 6 percent of schools as “failing,” no matter how well they may educate students. The Accountability Act, enacted mere hours after introduction in 2013, diverts tens of millions of dollars a year from public schools to private school scholarship funds.

ALL Kids, pre-K, SNAP offer models for success

The budget hearings painted a stark picture of Alabama’s challenges, but they brought good news, too. Lawmakers heard numerous examples of how investments in health care and education are paying off.

Alabama’s rate of uninsured children is among the South’s best, and ALL Kids is a big reason why. The program provides health coverage for children whose low- and middle-income households don’t qualify for Medicaid. ALL Kids was the country’s first Children’s Health Insurance Program, and it remains a national performance leader in children’s health coverage.

The Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) provides an exemplary community-based long-term care option for residents of Mobile and Baldwin counties. The state’s commitment to pre-kindergarten has created a model for early childhood education. And aggressive workforce training programs in K-12 and two-year colleges are boosting Alabama’s economic potential.

Medicaid Commissioner Stephanie Azar highlighted investments in long-term care reform and primary care reform. The statewide Integrated Care Network (ICN) has already launched its case management system, designed to steer more long-term care patients into home- and community-based services. On the primary care side, Alabama Coordinated Health Networks (ACHNs) will launch in seven regions this fall. That move will bring Medicaid decision-making closer to communities and emphasize preventive and coordinated care.

Buckner thanked DHR’s Food Assistance Division for ensuring Alabamians received benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) during the recent federal government shutdown. Facing a Jan. 20 deadline to distribute February benefits, employees worked nights and weekends to approve 1,700 SNAP applications.

Buckner also praised the Food Assistance Division for earning federal bonuses of $2.4 million for timely processing of applications and low error rates in benefit calculations. Unfortunately for Alabama, which has a highly efficient and accurate SNAP program, Congress ended future bonuses in the 2018 Farm Bill.

It’s time to invest in a brighter future

Successful investments like these aren’t “one and done.” Alabama must resume providing some state money for ALL Kids next year as full federal funding ends. PACE seeks to expand, but its requests have been rejected so far. Only one-third of Alabama’s 4-year-olds are enrolled in pre-K. And gearing up for the 21st century will require even bolder workforce development.

Treading water is not enough. Education, Medicaid and other vital services need more funding so they can do more than the bare minimum. Smart investments in these services will pay off in a stronger, healthier future for all Alabamians.

Policy director Jim Carnes, policy analyst Carol Gundlach and communications director Chris Sanders contributed to this post.

Alabama’s state higher ed funding cuts since 2008 are country’s third deepest

Alabama’s cuts to state higher education funding over the last decade are among the deepest in the country, according to a new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a nonpartisan research organization based in Washington, D.C. The funding decline persisted even as the state’s economy began to rebound from the Great Recession.

Since 2008, Alabama has slashed state higher education funding by 34.6 percent or $4,290 per student, CBPP found. The state’s cuts are the nation’s third worst by dollar amount and fifth worst by percentage. Nationally, the average cuts since 2008 are 16 percent or $1,502 per student.

Alabama’s inadequate public investment in higher education over the last decade has contributed to rising tuition prices, often leaving students with little choice but to take on more debt or give up on their dreams of going to college. Between 2008 and 2018, the average tuition at public four-year institutions in Alabama jumped by $4,329, or 69.8 percent – far outpacing the national average growth of 36 percent. These soaring costs have erected barriers to opportunity for young people across Alabama, particularly for black, Hispanic and low-income students.

“Pushing the cost of college onto students and their families will not make our state stronger,” Alabama Arise policy analyst Carol Gundlach said. “We must invest adequately in higher education to be able to build an Alabama where everyone has the opportunity to succeed.”

Americans’ slow income growth has worsened the college unaffordability problem. While the average tuition bill increased by 36 percent between 2008 and 2018, median incomes grew by just over 2 percent. Nationally, the average tuition at a four-year public college accounted for 16.5 percent of median household income in 2017, up from 14 percent in 2008.

In Alabama, a college education is even less affordable, especially for black and Hispanic families. In 2017, the average tuition and fees at a public four-year university accounted for:

• 21 percent of median household income for all Alabama families.

• 32.2 percent of median household income for black families in Alabama.

• 26.8 percent of median household income for Hispanic families in Alabama.

“The rising cost of college risks blocking one of America’s most important paths to economic mobility,” said CBPP senior policy analyst Michael Mitchell, the report’s lead author. “And while these costs hinder progress for everyone, black, Hispanic and low-income students continue to face the most significant barriers to opportunity.”

Financial aid has failed to bridge the gap created by rising tuition and relatively stagnant incomes. As a result, the share of students graduating with debt has increased. Between 2008 and 2015, the share of students graduating with debt from a public four-year institution rose from 55 percent to 59 percent nationally. The average amount of debt also increased during this period. On average, bachelor’s degree recipients at four-year public schools saw their debt grow by 26 percent (from $21,226 to $27,000). By contrast, the average amount of debt rose by only about 1 percent in the six years prior to the recession.

A large and growing share of future jobs will require college-educated workers. Greater public investment in higher education, particularly in need-based aid, would help Alabama develop the skilled and diverse workforce it needs to match the jobs of the future.

“All Alabamians, regardless of their income or where they grow up, deserve an opportunity to reach their full potential,” Gundlach said. “Our state should end tax breaks for large corporations and invest in making college more affordable for the students who need assistance the most.”

Medicaid expansion, end to grocery tax highlight Alabama Arise’s 2019 priorities

Medicaid expansion and legislation to end the state sales tax on groceries are among the top goals on Alabama Arise’s 2019 legislative agenda. More than 200 Arise members picked the organization’s issue priorities at its annual meeting Saturday, Sept. 8, 2018, in Montgomery. The seven issues chosen were:

- Tax reform, including untaxing groceries and closing corporate income tax loopholes.

- Adequate funding for vital services like education, health care and child care, including approval of new tax revenue to protect and expand Medicaid.

- State funding for the newly created Public Transportation Trust Fund.

- Consumer protections to limit high-interest payday loans and auto title loans in Alabama.

- Legislation to establish automatic universal voter registration in Alabama.

- Reforms to Alabama’s criminal justice debt policies, including changes related to cash bail and civil asset forfeiture.

- Reforms to Alabama’s death penalty system, including a moratorium on executions.

“Public policy barriers block the path to real opportunity and justice for far too many Alabamians,” Alabama Arise executive director Robyn Hyden said. “We’re excited to unveil our 2019 blueprint to build a more just, inclusive state and make it easier for all families to make ends meet.”

Alabama’s failure to expand Medicaid to cover adults with low wages has trapped about 300,000 people in a coverage gap, making too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to receive subsidies for Marketplace coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Expanding Medicaid would save hundreds of lives, create thousands of jobs and pump hundreds of millions of dollars a year into Alabama’s economy. Expansion also would help keep rural hospitals and clinics open across the state.

The state grocery tax is another harmful policy choice that works against Alabamians’ efforts to get ahead. Alabama is one of only three states with no sales tax break on groceries. (Mississippi and South Dakota are the others.) The grocery tax essentially acts as a tax on survival, adding hundreds of dollars a year to the cost of a basic necessity of life. The tax also is a key driver of Alabama’s upside-down tax system, which on average forces families with low and moderate incomes to pay twice as much of what they make in state and local taxes as the richest Alabamians do.