Many Alabamians have modified their work circumstances in recent months to reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19. But tens of thousands of people still must work in public-facing jobs that put them at increased risk of illness.

Front-line workers in grocery stores, hospitals and pharmacies perform necessary tasks to keep our communities functioning during the pandemic. The burden of facing those health risks is unevenly distributed, though. Workers in jobs like health care, food service and child care are disproportionately likely to be people of color or women. And state and national policy failures on COVID-19 are more likely to hit them the hardest.

Gender disparities and low wages increase risk

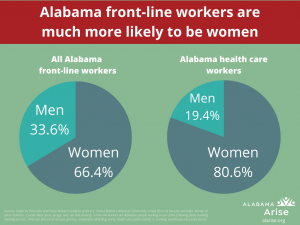

Differing employment levels in the health and retail fields particularly have forced more women to risk coronavirus infection. Two-thirds of Alabama’s essential workers are women, though women comprise just under half of the state’s total workforce.

Health care workers overall are much more likely to be women, and they face drastically heightened risk of infection at work. Among Alabama workers, women comprise 81% of health care workers and 89% of child care and social services workers. Jobs in these fields often require consistent exposure to large numbers of people.

Health care accounts for more than one in 10 jobs in Alabama. And the higher proportion of women in this field contributes to a gender-based disparity for COVID-19 exposure. In many cases, personal protective equipment (PPE) has run short for doctors, nurses and other health care professionals. This structural failure has forced many of these workers to reuse PPE, posing potentially severe health risks.

The wages and work conditions for essential front-line workers often don’t reflect the importance of their work. Many workers received higher hourly wages early in the pandemic, but now some employers have begun eliminating hazard bonuses. In the retail sector – already filled with low-wage jobs with sparse benefits – major employers like Amazon, Kroger and Target have stopped their wage bonuses.

Returning to work at unsustainably low wages amid a pandemic isn’t the only way many hard-working Alabamians are being squeezed. The state also has placed workers at risk of homelessness with an ill-timed wave of unemployment insurance (UI) benefits cutoffs coupled with the lifting of a two-month moratorium on evictions for nonpayment of rent. And a federally funded $600 weekly UI benefit increase during the pandemic will expire this month unless Congress renews it.

Racial disparities in employment and health coverage shape risk

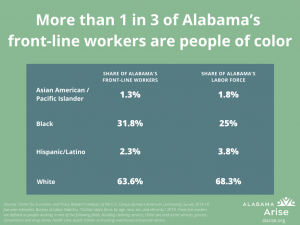

Structural factors leave Black and Latino Alabamians at increased risk from COVID-19. Black and Latino people account for a disproportionate share of workers in essential jobs. And because of long-term, systemic racism that creates barriers to regular health care, Black people are more likely to have underlying conditions that worsen coronavirus outcomes.

Even among essential workers, people of color are more likely to face heightened exposure in certain public-facing industries. In Alabama, the share of Black people working in grocery or convenience stores is two and a half times larger than in the U.S. workforce overall. The share of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who work in grocery and convenience stores is double their percentage of Alabama’s overall population.

Despite these elevated risks, Black and Latino Alabamians are far more likely than white people to lack health insurance coverage. And because Alabama hasn’t expanded Medicaid, Black and Latino residents are more likely to fall into the health coverage gap, earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to afford insurance. People of color make up 34% of Alabama’s population but comprise 49% of uninsured Alabamians with low incomes.

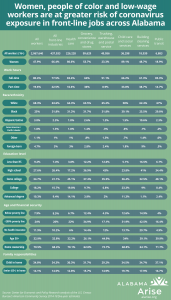

This table shows the disproportionate burden that women, people of color and low-wage workers face across several essential employment fields:

Unfortunately, the chart’s data cannot account for differing exposure rates based on specific jobs within those career fields. But given that women in medical fields often face bias inhibiting their promotion into supervisory roles, women are likely at greater risk of coronavirus infection than their high proportion in the health care industry indicates. And overall, people of color are more likely to work non-supervisory jobs with higher public exposure in many front-line fields.

Shortsighted policy choices harm the economy and virus containment

Refusal to expand Medicaid and attempts to slash UI benefits are harmful policy decisions that fly in the face of the reality of the pandemic. And the burden of these cruel choices falls more heavily on people who already face disadvantages in the labor market.

More than 600,000 people have filed UI claims in Alabama since the pandemic reached the state in March. Thousands of Alabamians are already losing UI benefits for refusing to return to work in conditions they see as unsafe. Each person prematurely knocked off the UI rolls loses not only the $275 monthly state benefits, but also the $600 monthly federal supplement guaranteed through July. Alabama is forfeiting millions of federal dollars as a result.

That money would help shore up flagging state revenues for education, health care and other vital services. It also would help people meet basic needs and limit the coronavirus’s spread during an unprecedented economic and health crisis. Forcing people back to workplaces while COVID-19 is still rampant is a dangerous attempt to restore Alabama’s inequitable economic structure.

Alabama should move forward, not return to past failures

The pandemic has shined a light on many of Alabama’s policy mistakes. The state can take this opportunity to fix harsh, shortsighted policies that devalue and harm Alabamians. And our leaders must take the lead on implementing helpful policies because of a lack of comprehensive federal action. The U.S. Department of Labor has issued no guidance allowing workers in high-risk groups to stay home and retain benefits. And the department has not reinforced health and safety protections for workers whose employers don’t take proper coronavirus precautions.

As a result, many older adults, cancer survivors and immunocompromised people face a stark choice between their lives and livelihoods. They must either subject themselves to a higher chance of death from COVID-19 or risk hunger and homelessness when the state cuts off UI benefits. Black and Latino people, women and struggling families will bear the brunt of this callous undermining of the safety net.

Alabama can and should do better. Instead of forcing people back into workplaces prematurely, lawmakers should fix failed policies like the 2019 cuts to UI benefits. Gov. Kay Ivey should expand Medicaid to ensure everyone can get the life-saving health care they need. And our state should abandon the impulse to punish people for inability to find work, especially during a deep recession. Instead, Alabama should enact policies that support and value people both while they work and when they lose their jobs.